A cGDP Primer: New Distribution Models For Life Science Supply Chains

By Carla Reed, president, New Creed LLC

The life sciences industry has undergone many changes over the last decade, with consolidation, mergers, and acquisitions across both small and large pharmaceutical and biotech companies. One result of these changes is complex supply chain models, with a combination of in-house and outsourced research, product development, and commercial operations. The level of complexity has presented challenges for stakeholders and their supply chain partners: suppliers of materials, components, and packaging, as well as contract research (CRO), contract manufacturing (CMO), and logistics service providers.

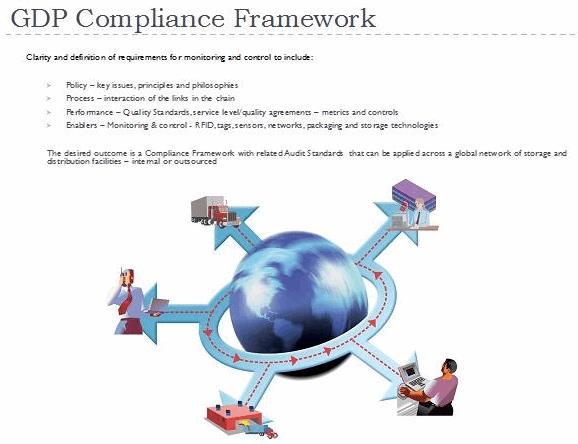

Networks of storage facilities are connected by a variety of transportation modes, across extended geopolitical regions. It is no longer sufficient to manage supply chain quality and compliance activities in a relatively controlled environment “inside the box.” Ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of API, raw materials, ingredients, and related packaging components requires oversight and compliance across the many links in the chain — the dynamic environment of global distribution. Risk factors abound, not the least of which is an increase in diversion, counterfeit, and corruption of the legitimate life sciences supply chain.

Global regulatory bodies have responded to these challenges, requiring digital audit trails in the form of mass-serialization — e-pedigree and formalized track and trace programs. Further complicating matters is the recent increase in oversight by industry groups and regulators, enforcing guidelines for establishing, monitoring, and controlling storage and distribution operations.

For most of these guidances and related materials, the primary focus is the safe and secure “state” of the product as it is moved through the transformation process, with conversion taking place in multiple locations. The majority of these process steps fall under the governance of cGMP, which in most cases is already implemented in even the most immature locations. As such, the extended focus of current good distribution practices (cGDPs) aligns well with the current quality systems in place for best–in-class life sciences companies (and their partners).

For most of these guidances and related materials, the primary focus is the safe and secure “state” of the product as it is moved through the transformation process, with conversion taking place in multiple locations. The majority of these process steps fall under the governance of cGMP, which in most cases is already implemented in even the most immature locations. As such, the extended focus of current good distribution practices (cGDPs) aligns well with the current quality systems in place for best–in-class life sciences companies (and their partners).

- The additional requirements of the cGDP guidelines fall into two primary categories: Storage facilities

- Distribution and transportation

The following sections will explore these categories in greater detail.

Storage Facilities

In common with manufacturing locations, the storage environment is relatively static, with related quality standards, standard operating procedures, and process-level best practices. Specific requirements for cGDP compliance include inbound materials management, outbound shipment management, and quality system.

Inbound Materials Management

Traditional manufacturing operations include receipt of raw materials, API, packaging components, and related supplies into the manufacturing facility, as well as the movement and receipt of finished goods. This integrated closed-loop process includes material movement into a warehouse or distribution center, with clearly defined operating procedures and controls. In the more “dis-integrated” outsource model, the activities and controls that take place include the receipt of raw materials, interim storage, and transshipment to manufacturing locations and outbound movement of finished products to the point of consumption.

These interim storage locations are, in many cases, controlled and operated by third-party logistics companies, with a commercial focus on the material handling activities and related consolidation and transportation processes. In order to ensure that the quality, safety, and security of all raw materials and products is maintained, it is necessary to have clearly defined service level agreements (SLAs), ensuring that all activities that take place are in compliance with the guiding principles of cGDP.

Material and product receipt is a critical process and will have a direct impact on the level of detail that is available for review and analysis. (This is particularly important in the event of a problem or product recall.) Product inspection is important at the actual time of receipt, versus the common practice where goods are received at the dock door and placed into an interim location for later inspection and data capture. Best practices include the receipt of an advanced shipment notification from the source location — this defines the material at the item level and provides special handling or storage requirements. Advanced notification facilitates streamlined process and data capture and also enables verification of authenticity of materials prior to receipt. Another advantage of this practice is the ability to preassign a storage location for the material, whether it is for interim or longer-term storage. In particular, it is critical to ensure that environmental control is planned for — to include specific humidity and temperature control for all materials.

Outbound Shipment Management

Preparation for shipment from storage locations is equally important, taking into account any potential hazards that could impact the quality, safety, and integrity of the materials or products. As appropriate, protective packaging, tamper evident seals and shipment monitoring, and alerting technology should be provided. A clearly defined SLA should take into account risk factors based on a combination of origin and destination pairs, as well as security risks that need to be considered.

Quality System

A core requirement of cGDP is that all participants in storage and distribution should have a formalized quality system that sets out responsibilities, processes, and risk management principles. As an extension of the focus on manufacturing operations, this should provide standards and guidelines for ensuring compliance under the following categories:

- Documentation: Clear, concise written communication through documentation that prevents errors from spoken communication (lack of ambiguity)

- Personnel: Competent, trained, and empowered personnel to carry out all the tasks that take place across the storage and shipment lifecycle (internal and outsourced)

- Premises and equipment: Clean, secure, and well-maintained premises, equipment, and transportation devices for the safe handling, storage, and transportation of materials and product

- Complaints, returns, and recalls: Documented process for handling complaints, returns, suspected falsified medicinal products, and recalls

Distribution and Transportation

Traditionally, the areas of product and material distribution and transportation have included a combination of internal and external resources — people, premises, and equipment. With the complexity of global distribution, these functions increasingly are outsourced to specialized service providers who have the expertise, experience, and global reach to meet the needs of a complex set of distribution models.

cGDP guidelines provide a baseline for the outsourcing of distribution operations, with clearly defined requirements for third-party provider qualification. In addition, these guidelines extend into the operational management of transportation, directly or through a third-party network.

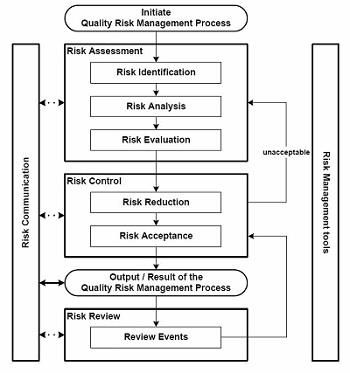

Risk Assessment

One of the cGDP guiding principles is to adopt a risk-based approach to all process steps, from shipment planning through execution. In order to perform this risk assessment, it is necessary to take into account the combination of factors that could impact the integrity of the material or product being transported. These include risks from variations in temperature, humidity, altitude, vibration, or any other factors that could impact the integrity of the material.

Additional risk factors should then be evaluated, taking into account stability data for raw materials, API, drug substance, and drug products. These fall into the category of time and temperature sensitive materials, requiring an additional level of oversight and control.

Many life sciences products have special handling requirements — for example, temperature, altitude, and vibration control. This level of detail should be included in the risk assessment and shipment plan, ensuring that the appropriate packaging, temperature control, and data logging devices are included in the shipment plan. Also, it is critical to ensure that resources are available to monitor, manage, and remediate when things do not go according to plan!

Mitigation strategies include providing protective packaging and data loggers, and ensuring that the process steps across the chain of custody and control are clearly defined — and that all risk factors planned for. ICH 9 defines a risk assessment approach that can be followed for shipment planning, taking into account risk factors and developing a process model to include product protection, communication across the chain of custody, monitoring, and reporting. See Figure 1 below.

Risk Assessment: Shipment level based on new item/shipping location or other risk factors

Figure 1

Risk Remediation

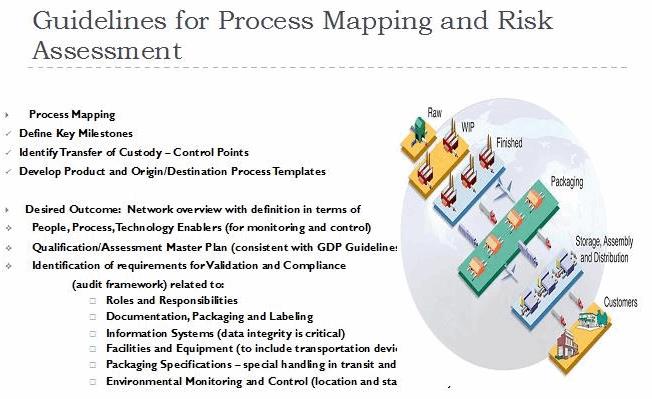

Identification of potential risk factors during the risk assessment will enable a clearly defined shipment plan, at the item and origin/destination level. Additional risk mitigation should include a review of each of the process steps in the shipment lifecycle, identifying interim transshipment locations and entities across the chain of custody.

The shipment plan should include the definition of elapsed time between each of these links in the chain, and related check and choke points across the end-to-end shipment lifecycle. A best practice includes mapping the process steps to include graphic illustrations of handoff points across the physical movement of the shipment.

Figure 2

The process map should include definition of each of the activities, to include regulatory compliance requirements, associated requisite documentation, communication between origin and destination parties, and any restrictions and/or risks that should be planned for. In addition, it is important to take into account the financial transactions that take place, and the impact of any delays that could compromise product integrity.

Monitoring and control of the shipment at key points in the shipment lifecycle should be planned for and included in any SLAs with third-party service providers. These could include, but are not limited to:

- Shipment management: environmental monitoring and control

- Oversight through third parties: control tower concept

- Transshipment: interim shipping and material handling across the chain of custody

- Industry compliance: documentation management and control

- Import: export and regulatory compliance requirement

- Delivery: receipt and inspection at final point in chain of custody

Figure 3

Although the majority of the logistics-related activities can be outsourced, it is important to ensure that management and control (oversight) is retained for all distribution activities, to include:

- Resources — definition and understanding of roles and responsibilities

- Internal qualified person (QP)

- External QP

- Cross-functional team members across the chain of custody

- Control points

- Communication

- Metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs)

- Corrective and preventative action (CAPA)

With proper implementation and controls, the chain of custody can be established and secured, creating a high degree of confidence on the origins and authenticity of an item. This addresses some of the concerns related to safety and security of all medicinal products and related API and materials as they are transported across the supply chain.

Shipment planning, management, and control are the first steps to ensuring cGDP compliance. During the risk assessment process, material handling risk and remediation is planned for. However, there are other elements that should be taken into account to ensure a safe and secure supply chain, which subsequent articles in this series will explore.

References / Further Reading:

- GDP Guide EU 2013_2

- GDP 2015-10 Annex 15

- USP 1070/1197 (and subsequence unpublished 1083)

- WHO Guides – API and Storage Practices

- QAS – Draft WHO GDP Perspective

- PE-011-1 – PIC/S GDP Guide

- EU Guideline on Good Distribution Practice of Medicinal Products for Human Use, 2011 (for public consultation)

- PDA Technical Report No. 39, Guidance for Temperature-Controlled Medicinal Products: Maintaining the Quality of Temperature-Sensitive Medicinal Products through the Transportation Environment, 2007.

- PDA Technical Report No. 46, Last Mile: Guidance for Good Distribution Practices for Pharmaceutical Products to the End User, 2009.

- PDA Technical Report No. 52, Guidance for Good Distribution Practices (GDPs) for the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain, 2011.

- PDA Technical Report No. 53, Guidance for Industry: Stability Testing to Support Distribution of New Drug Products, 2011.

- PDA Technical Report No. 58, Risk Management for Temperature Controlled Distribution, 2012.

- ICH Q9 – Quality Risk Assessment

- ICH Q10–Pharmaceutical Quality System

About The Author:

Carla Reed is a supply chain professional with more than 20 years of experience in supplier engagement, manufacturing, emerging market development, outsourcing, global trade, regulatory compliance, storage, and distribution. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at newcreed11@gmail.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.

Carla Reed is a supply chain professional with more than 20 years of experience in supplier engagement, manufacturing, emerging market development, outsourcing, global trade, regulatory compliance, storage, and distribution. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at newcreed11@gmail.com or connect with her on LinkedIn.