Compliance Or Adherence? How To Approach cGMP Regulations In The 21st Century

By Ajaz S. Hussain, Ph.D., Insight, Advice & Solutions LLC

At the beginning of the 21st century, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) launched several initiatives to help improve the efficiency and reliability of pharmaceutical operations, and via ICH these efforts were then extended internationally.1 However, operational challenges persist and continue to be visible in external failures such as drug shortages, recalls, warning letters, and import alerts. The FDA has recently taken additional steps to achieve the goals it outlined in the 21st Century initiative.2 Over the past couple of years, a growing cluster of deviations — breaches in the assurance of data integrity — have gained prominence, in part due to improved detectability, and this has led to an erosion of trust.3

Why does compliance with these good practices present such a significant challenge for the pharmaceutical industry? Reflecting on insights accumulated over the past two decades while working at FDA4,5 and more recently in the private sector6-8, I would suggest that we — as a community of professional practitioners — are not adequately accounting for certain human behaviors in our business and regulatory practices.

This article seeks to improve awareness of this urgent and pressing need, and it invites a discussion on ways to improve human-centricity in the pharmaceutical industry’s operational practices. Additionally, progress and trends in process analytical technology (PAT) and in the adoption of quality by design (QbD) which are both part of the solution, are discussed.

Word Choice Matters

The words we use influence the way we think, organize information, make decisions, and behave. Consider two commonly used words in our vocabulary: compliance and adherence. In pharmaceutical operations, compliance is used to describe the behavior of following written instructions or operational routines (SOPs). In healthcare, the noun adherence describes the behavior of following written instructions for taking medications (prescriptions). In the cGMP context, would you consider compliance and adherence to be synonymous?

On its website page “Facts About the Current Good Manufacturing Practices,” FDA writes that “Adherence to the CGMP regulations assures the identity, strength, quality, and purity of drug products by requiring that manufacturers of medications adequately control manufacturing operations.”9 In this context, is adherence synonymous with compliance? Alternatively, is it a subtle reminder of an important principle?

Note: The noun adherence is related to the verb adhere, meaning “to hold fast or stick by” or “to give support or maintain loyalty.” Compliance is the noun form of the verb comply, which means “to do what you have been asked or ordered to do” — Compliance is the act of submitting, usually surrendering power to another.

In healthcare, the noun adherence is preferred, write Lars Osterberg and Terrence Blaschke, “because ‘compliance’ suggests that the patient is passively following the doctor’s orders and that the treatment plan is not based on a therapeutic alliance or contract established between the patient and the physician.”10 Adherence to medications is squarely in the patients’ self-interest.

The rate of adherence to prescription medications, particularly in chronic conditions, is dismal, perhaps owing to a legacy compliance mindset. Changing this behavior is incredibly difficult, as if humans have an innate immunity to change, Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey argue in their book of the same name: “… when doctors tell heart patients they will die if they don’t change their habits, only one in seven will be able to follow through successfully.... our individual beliefs — along with the collective mindsets in our organizations — combine to create a natural but powerful immunity to change.”11 Should it surprise us that deviations from established pharmaceutical operating routines (SOPs) are widespread12 and such a significant challenge?

So why does the FDA use the word adherence when referring to cGMP regulations? To emphasize that adherence to cGMP regulations provides ample flexibility to design and implement policies and procedures. Such systems are required to “assure the identity, strength, quality, and purity of drug products” in any facility and should account for, among other things, specific human factors therein.

It is the responsibility of company management and leaders to design and implement processes and procedures that are easy and even enjoyable to comply with. Unfortunately, in some companies, the quality management system (QMS) is just a folder of policies and procedures, often put together using a cut-and-paste approach — i.e., without design or system thinking. Such disregard can eventually trigger a regulatory demand for cGMP remediation. Are we not underestimating human immunity to change?

Reasons for Nonadherence

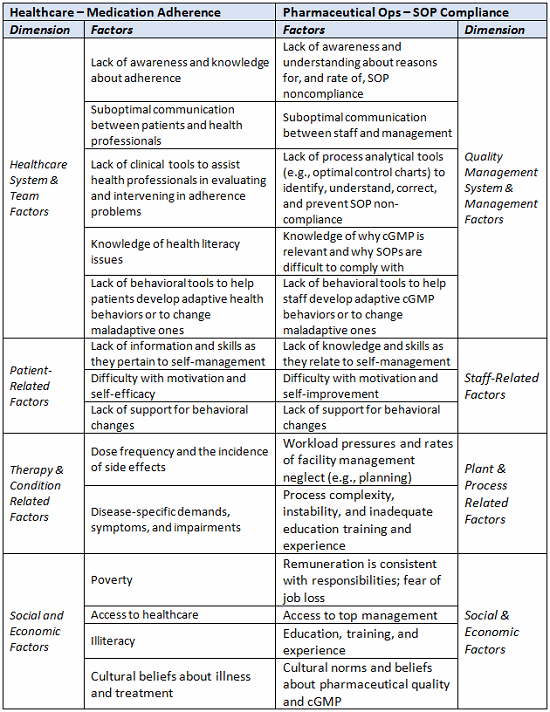

A considerable amount of research has been conducted to identify correlates and predictors of medication adherence and nonadherence, and it is useful to consider its relevance to noncompliance with SOPs in pharmaceutical operations. The table below lists five interacting dimensions of nonadherence13 and draws parallels to factors involved in the failure to comply with SOPs. Clearly, the list of factors is not comprehensive; it is only intended to highlight some similarities between the two challenges.

Table 1: Comparing Factors for Medical Nonadherence with those of cGMP Noncompliance

Patient-Focused Manufacturing, Quality, and Regulatory Solutions

The FDA’s Pharmaceutical Quality for the 21st Century initiative aimed, in part, to reduce the reactive approach to regulatory compliance that is ingrained into the system. Although there has been some progress, many challenges remain. Early in 2015, the FDA’s new Office of Pharmaceutical Quality (OPQ) was established within the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), and it is expected to achieve, more comprehensively, the goals outlined by the agency in its 21st Century Initiative. The FDA has noted some challenges that continue:2

- Product recall and defect reporting data demonstrate unacceptably high occurrences of problems attributed to inherent defects in product and process design.

- There have been alarming shortages of critical drugs over the past few years.

- The number of postapproval supplements has increased over the past decade, owing to a burdensome regulatory framework that inhibits industry’s ability to optimize and improve processes.

- Current regulatory review and inspection practices to be “one size fits all,” which in some cases fails to consider specific risks to the consumer or individual product failure modes.

- There are no formal benchmarks for the current state of pharmaceutical quality, and inadequate quality surveillance difficulty to making on risk.

- Inspection and functions disjointed; inspections are not well-connected to knowledge gained from product and vice versa.

In the Federal Register Notices dated March 12, 2015, FDA announced its participation in a conference entitled ‘Mission Possible: Patient-Focused Manufacturing, Quality, and Regulatory Solutions. It should be obvious that patient-focused manufacturing, quality, and regulatory solutions demand an adequate emphasis on staff/operator-centric quality management systems, policies, and procedures.

A case in point is our casual attitude towards the 21 CFR 211.25: “Each person engaged in the manufacture, processing, packing, or holding of a drug product shall have education, training, and experience, or any combination thereof, to enable that person to perform the assigned functions.”5 Shouldn't staff and their supervisors reliably comply with written SOPs when provided with appropriate education, training, and experience? Given that pharmaceutical processes are required to be validated, complying with SOPs should yield predictable outcomes. How often is that the case? Maybe 70 to 90 percent of the time? That is not often enough!

When a manufacturing process is not predictable, human error is often assigned the immediate blame (though what is the root-cause?), and sufficient correction is to retrain or modify a SOP and retrain. However, when this occurs repeatedly, an operator can lose his/her job, or it can open the door to an individual and systematic set of irrational behaviors — and sometimes this leads to breaches in the assurance of data integrity.

Confronting Our Immunity to Change

In their book, Kegan and Lahey describe the following three dimensions of the immunity to change:11

- Change-prevention system, which thwarts challenging aspirations

- Feeling system, which manages anxiety

- Knowing system, which organizes reality

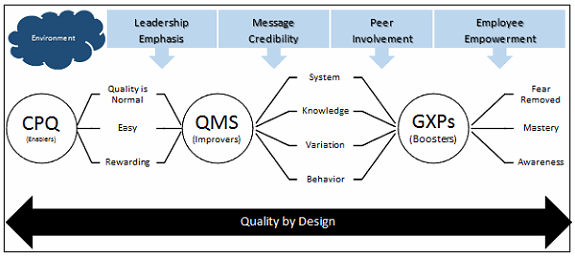

Employee empowerment is in need of attention (feeling system). It begins with senior leaders making adherence to cGMP regulations and compliance with SOPs the “normal thing to do,” easy to do, and also rewarding (see Figure 1). Other employees look towards the leaders to guide and support them.

Figure 1: The culture of pharmaceutical quality — connect-the-dot framework

Good practices include management actions to provide support and resources, asking questions to ensure optimal design, and efficient implementation of SOPs, which should be designed in combination with targeted training. Given a set of starting conditions (e.g., raw material certificates of analysis, and equipment), even a complicated process should be reproducible and should deliver the expected results. (We are in operations mode, not in research, after all). Processes that do not are considered complex.

Interactions and emergence characterize a complex process. Merely following a SOP with complex processes will not reproducibly achieve expected results. Right first time (RFT) rates for pharmaceutical processes can be small, suggesting process complexity.

A failure rate of 5 percent (or even less) should not be considered low because in certain environments and company cultures it still can have a devastating impact on behavior. Management that does not openly acknowledge the need for high RFT rate (during development) is perhaps trapped in a “file first and figure it our later” mindset. Then, when they fail to recognize the actual RFT during routine operations (the change-preventing system), it can lead to rationalization within an organization. Phrases such as “this is FDA approved” or “this process is validated” when heard in company discussions should raise a red flag!

The knowing system (epistemology: how do you know what you know?) is critical. It calls for leaders to ask the right question at the right time. Traditional regulatory defaults — such as a scale-up factor of 10x or three batches for process qualification — can be an easy reminder to ask the right questions, but how do you know that 10x is the optimal option for a particular product/process? The knowing system should cover the entire life cycle, from proper development and regulatory review to effective process validation, technology, knowledge transfer, and continued process verification. The knowing system should include a special reminder to improve awareness of how adherence to cGMP and compliance with SOPs addresses residual uncertainty.

Getting it Right First Time in the 21st Century

Commitment to achieve the goals of the FDA’s 21st Century Initiative requires concerted efforts in multiple dimensions — on the stubborn immunity to change (as discussed above), as well as on our methodologies and our technologies. Progress in these three dimensions is palpable.

Integrating generic CMC (chemistry, manufacturing, and control) review within OPQ/CDER/FDA is already changing questions posed to sponsors; questions about patient-related failure modes and manufacturability are now more prominent, and that may come as a surprise for some companies. Issues now being raised by FDA during CMC review signal that the methodology for quality by design (QbD) should be a more serious focus during development and, perhaps, represent a strong message against the practice of “file first and figure it out later.”

If this trend continues (and regulator heterogeneity is sufficiently minimized), it can offer a significant competitive advantage for those companies that have advanced their business practices to implement QbD methodology (e.g., as per FDA PAT, ICH Q8-11, and 2011 process validation guidance) efficiently in their development program. The business impact should be most significant for new breakthrough drugs (where product development and CMC review can often be on a critical path and time crunch), complex generics, and first generics.

The FDAs strong support for application of new technology in pharmaceutical manufacturing — particularly as it pertains to continuous production — is broadly evident. Its summary review of regulatory action on Vertex’s NDA 206038 indicates why characterizing this 2015 approval as a tipping point” would not be an exaggeration:

The manufacturing process for product employed Quality-by-Design (QBD) process for the development of the product, manufacturing process, and control strategy. A fully continuous drug product manufacturing process was applied to the manufacture of the product, which is a unique and a new process.14

A new manufacturing process included in an NDA submission is a pleasant surprise, indeed! Moreover, it also provided for a rapid QbD development of product, manufacturing process, and control strategy.

The Vertex NDA implicitly provides reassurance that a PAT-based manufacturing and control strategy can address several ontological and epistemological gaps that exist today (in FDA’s Inactive Ingredient Database, the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention, and more broadly). PAT provides a way to measure, monitor, and control physical quality attributes such as excipient functionality and offers efficient solutions for many frustrating issues such as blend uniformity testing.

Vision 202015 appears to be on track, and significant business opportunity is within grasp in the next three+ years. This vision included technical capabilities to get pharmaceutical manufacturing right first time. Perhaps the growing number of breaches in data integrity help to remind us of our cognitive biases and blind spots, more because we cannot dismiss the possibility that many such cases may be due to improved detectability. This realization should prod us to overcome immunity to change and to look for practical solutions in disciplines such as behavioral economics that can improve our practices.16

Rapid, comprehensive QbD development of solid dosage forms, process, and control system in a PAT-based continuous manufacturing system is an attractive option for both industry and regulators. Fully integrated drug substance and product continuous production systems are also expected to gain momentum. Improved assurance of quality, smaller footprints, material savings, and a relatively lower environmental impact are among the important reasons why adoption of these systems will increase with continued regulatory encouragement. Broader adoption of PAT-based continuous manufacturing system by a major brand and generic drug makers and CDMOs should continue over the next three years.

Perhaps an even bigger incentive will turn out to be the “c” in cGMP, which has started to trend in the direction of process control, statistical confidence, and continued process verification. When this is accounted for in FDA’s risk-ranking of facilities, it would be a significant driver for Six Sigma level of assurance for pharmaceutical quality.

An excellent opportunity for continuous manufacturing also exists in injectables, and there is an urgent need for it, so as to mitigate the risk of drug shortages. Although not prominent today, we should expect to see more progress in injectable manufacturing over the next three years.

The pharmaceutical education and training systems in the United States and Europe have been advancing to support this transition, though additional efforts are needed to expand such opportunities. Programs for India, China, and other emerging regions should be a high priority.

Conclusion

Adherence to cGMP regulations provides ample flexibility to design and implement effective policies and procedures that are easy to comply with, and that can improve when necessary. Such systems assure the identity, strength, quality, and purity of drug products. Regulatory requirements are minimal requirements, and companies need to move beyond regulatory check-the-box and cut-and-paste exercises. Aiming high — and taking ownership and responsibility for quality — is essential.

To get it right first time in the 21st century, let’s remember Einstein’s challenge that we will never solve the problems tomorrow with the same order of consciousness we are using to create the problems of today! When we chose not to put on blindfolds and recognize that pharmaceutical quality is like an elephant in the dark, then the Persian poet and scholar Rumi’s centuries-old strategy still applies: “If each of us held a candle there, and if we went in together, we could see it.”

This article will be part of the CPhI 2016 Annual Report, which will be released during the CPhI Worldwide event in Barcelona (October 4-6, 2016).

References:

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Pharmaceutical cGMPs for the 21st Century — A Risk-Based Approach (Final Report). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/Manufacturing/QuestionsandAnswersonCurrentGoodManufacturingPracticescGMPforDrugs/UCM176374.pdf. September 2004. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- U.S Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Office of Pharmaceutical Quality. FDA Pharmaceutical Quality Oversight: One Quality Voice. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/UCM442666.pdf. December 2015. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Draft Guidance for Industry: Data Integrity and Compliance with CGMP. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm495891.pdf. April 2016. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- Hussain, A. S. How Did the PAT/QbD Journey Begin? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=II0_nE6hr9c. January 18, 2016. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- Hussain, A. S. “The Nation Needs a Comprehensive Pharmaceutical Engineering Education and Research System Pharmaceutical Technology. September 2005.

- Hussain, A. S. “ of Pharmaceutical Quality: Connecting the Dots Biopharma Asia. September/October 2015.

- Hussain, A. S. “ of Pharmaceutical Quality Management System Biopharma Asia. November/December 2015.

- Hussain, A. S. “ of Pharmaceutical Quality: Development Biopharma Asia. March/April 2016.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Facts About the Current Good Manufacturing Practices (CGMPs). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/Manufacturing/ucm169105.htm. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- Osterberg, L., and Blaschke, T. “Adherence to Medication New England Journal of Medicine, 353(5), pp.487-497. 2005.

- Kegan, R. and Lahey, L.L. Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock Potential in Yourself and Your Organization. Harvard Business Press. 2009.

- Anand, G., Gray, J., and Siemsen, E. “Decay, Shock, and Renewal: Operational Routines and Process Entropy in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Organization Science, 23(6), pp.1700-1716. 2012.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42682/1/9241545992.pdf. 2013. Accessed August 9, 2016.

- Chowdhry, B.A. US FDA Summary Review of Regulatory Action: NDA 26038; Orkambi®, Vertex Pharmaceuticals.http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2015/0206038Orig1s000SumR.pdf. June 2015. Accessed August 25, 2016.

- Hussain, A.S. A 21st Century Fable about Pharmaceutical Quality and Preventing a Clash of Cultures. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/21st-century-fable-pharmaceutical-quality-preventing-hussain-ph-d-. September 13, 2015. Accessed August 25, 2016.

- Hussain, A.S. “Chemometrics, Pharmacometrics and Econometrics: Dimensions of Quality by Design.” Swiss Pharma, 34 (2012) Nr. 6; 9-11.

About the Author:

Ajaz Hussain, Ph.D. distributes time between his consulting practice (Insight, Advice & Solutions LLC) and his role as president of the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Technology and Education (NIPTE). He trained as a pharmacist at the Bombay College of Pharmacy in India and received his doctoral degree from the University of Cincinnati. His career path is diverse — academician, FDA regulator, senior executive (in the pharma and tobacco sectors), and now an advisor and consultant with support for academia. He is passionate about making high pharmaceutical quality affordable and shares his view on the topic around the world and his LinkedIn page.

Ajaz Hussain, Ph.D. distributes time between his consulting practice (Insight, Advice & Solutions LLC) and his role as president of the National Institute for Pharmaceutical Technology and Education (NIPTE). He trained as a pharmacist at the Bombay College of Pharmacy in India and received his doctoral degree from the University of Cincinnati. His career path is diverse — academician, FDA regulator, senior executive (in the pharma and tobacco sectors), and now an advisor and consultant with support for academia. He is passionate about making high pharmaceutical quality affordable and shares his view on the topic around the world and his LinkedIn page.

About CPhI Worldwide:

CPhI Worldwide, together with co-located events ICSE, InnoPack, P-MEC, and FDF, hosts more than 37,000 visiting pharma professionals over three days. Over 2,500 exhibitors from more than 150 countries gather at the event to network and take advantage of more than 100 free industry seminars. For more information, visit www.cphi.com/europe.