Effective Risk Management: A Catalyst For Quality Performance

By Bikash Chatterjee, CEO, Pharmatech Associates

When we think of risk in the context of drug development and manufacturing, it is human nature to associate any risk-based approach with adding risk to the decision or process. However, when the FDA first introduced the concept of using risk as a component of the new definition of quality in 2004,1 the vision was to manage risk by coupling it with scientific understanding of process and product design for optimal product performance.

When we think of risk in the context of drug development and manufacturing, it is human nature to associate any risk-based approach with adding risk to the decision or process. However, when the FDA first introduced the concept of using risk as a component of the new definition of quality in 2004,1 the vision was to manage risk by coupling it with scientific understanding of process and product design for optimal product performance.

This guidance laid the foundation for two important concepts that influence how we develop and guarantee the quality of our drug products today. The first is that a structured risk framework during drug development and commercialization allows us to move away from an inspection-and-testing definition of quality and focus on what is truly critical to the product’s performance. The second is that quality must evolve from its traditional role as an inspector to one of a collaborator, infusing the drug development process with a clear understanding of quality considerations. As the product moves through the development and clinical processes, a quality management system (QMS) must be structured to reinforce the intelligent use of risk and to identify and evaluate the quality issues within its framework.

Challenges Of Quality Risk Management

When used as a foundational component within major systems, quality risk management (QRM) has a significant impact on a QMS. The problem is that today’s QMS are so much more complex to design and administer than the systems of even a decade ago.

For example, established pharma companies historically applied a vertical development and business model, handling everything from molecule identification to commercial introduction internally through their own service groups and facilities. Most QMS in place today are based upon that legacy model.

However, the discovery and development paradigm has become multifaceted. Collaboration development agreements among pharma organizations test the basic tenets of what is reasonable in terms of supplier qualification. Outsourced clinical manufacturing services challenge the processes surrounding change control, deviation, and lot release. Outsourced characterization and stability testing bring into question how to appropriately manage data integrity, oversight, and approval. In the absence of an embedded risk management philosophy, a conventional QMS will either implode under a sea of deviations or grind the development process to a halt.

Guidance For Understanding Risk

The two landmark best-practice guidances issued by the International Committee on Harmonization (ICH) are ICH Q9 and Q10. ICH Q92 describes a framework for risk management that consists of four major elements: risk assessment, risk control, risk review, and risk communication.

ICH Q103 presents a framework for the new definition of quality. It references utilizing risk management as a proactive approach to identifying, scientifically evaluating, and controlling potential risks to quality, thereby facilitating continuous improvement of product quality throughout the product lifecycle.

The Core Quality Systems And Risk

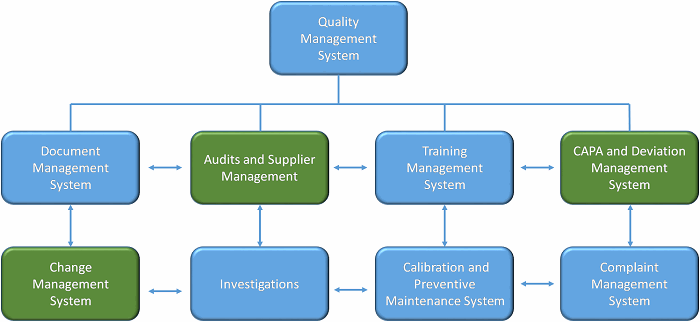

When considering which quality systems could benefit from a formalized quality risk management (QRM) component, systems that require a quality judgment can deploy risk assessment tools to improve the consistency of decision-making, and manage uncertainty. The major quality systems that benefit from QRM are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Major quality systems that could leverage QRM

Let’s examine three of these systems — deviation management, change management, and audits and supplier management — to better understand how QRM can be advantageous.

Deviation Systems

Deviation systems, sometimes called non-conformance systems, are essential for reinforcing the GMP component of a QMS. The challenge with most deviation systems is the uneven application of the system. In the absence of a prescribed framework for evaluating the quality impact, the quality decision defers to the quality function’s level of compliance tolerance.

Our firm conducted a survey across pharmaceutical manufacturing organizations and determined that a simple deviation costs an organization an average of $2,000 per incident. More complex deviations that require extensive investigations can cost up to $10,000 to complete — not including lost materials or supply interruption costs. Some firms can have 1,200 or more deviations on an annual basis, which translates to a substantial cost of poor quality.

Even so, the escalation path from an event or incident to deviation should not be automatic. A deviation is only required when there is an impact to the QMS or a potential for product quality impact.

Structured decision-making is the first opportunity to avoid non-value-added quality overhead to an event. One effective means to foster more consistent event evaluation is to provide a decision table for personnel to use when they encounter an excursion. For instance, if a process step is missed within a procedure, is it automatically a deviation? A decision rubric could aid the evaluator in determining if an escalation path is required. Consistent decision assessment tools are the simplest application of risk management.

Another QRM-based approach to determine whether a deviation is required is to evaluate the event using a simple heat map comparing severity against probability of occurrence. The use of risk assessment tools minimizes the subjectivity that can cripple most development and commercial organizations and lays the foundation for knowledge management. If excursions are dealt with consistently, the organization’s ability to recognize deviations and effectively deal with them improves dramatically. Some companies realized a 75 percent reduction in non-value-added deviations by employing some level of structured QRM in the deviation process. While this doesn’t guarantee a favorable result in a compliance audit, compliance exposure is greatly reduced by utilizing a structured decision-making process.

Change Management

In established quality organizations, change management systems are notoriously unreliable, because understanding what is required to make a qualified change is an area of the QMS where subjectivity is often the greatest. Many change management/control systems utilize a tiered structure with two to three levels of changes. Most procedures attempt to broadly define what could fall within each level.

One way to drive out subjectivity is to require the use of a System Impact Assessment (SIA). An SIA is a simple structured decision-making tool that assesses the potential for product quality risk. Some firms characterize product quality risk as SISPQ, which stands for safety, integrity, strength, purity, and quality. Others define product quality as SQIPP, which stands for safety, quality, integrity, purity, and potency. Regardless of the definition, having an agreed-upon criteria and an impact assessment tool to evaluate the proposed change against SISPQ/SQIPP is an effective means of fostering uniformity.

Audits And Supplier Management

One of the biggest challenges facing most quality organizations is providing oversight and control when using a contract service provider (CSP). Organizations rely upon a combination of audit programs and contractual agreements, such as quality and supplier agreements, to define and manage work that is outsourced. Using a risk assessment tool to evaluate the required criteria for qualifying a CSP is an effective means of determining which QMS system weaknesses are appropriate GMP risks to accept.

QRM principles can be extended further to the overall decision-making process. Some level of executive oversight governs most CSP engagement decisions. Using a structured decision-making tool such as a Pugh Matrix, or a structured analytical decision-making approach such as Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) can allow the organization to balance quality, technical, schedule, and financial risks associated with engaging a CSP.

Conclusion

Today’s model for drug development and commercial manufacturing is based upon leveraging external expertise, capabilities, and geography. The complexities of integrating these strategies can significantly impact an organization’s QMS effectiveness. A structured QRM framework as part of the core systems (deviation management, change control, and audits/supplier management) integrates a consistent methodology that drives quality decision-making while providing a sound means for evaluating technical, quality, and financial risks during development. World-class organizations have realized that QRM can be the catalyst for organizational performance across the product development lifecycle by facilitating development collaboration between the technical and quality functions up through commercial execution.

References:

- Pharmaceutical cGMPS for the 21st Century — A Risk-Based Approach

- ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management

- ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality System

About The Author

Bikash Chatterjee is president and chief science officer for Pharmatech Associates. He has over 30 years’ experience in the design and development of pharmaceutical, biotech, medical device, and IVD products. His work has guided the successful approval and commercialization of over a dozen new products in the U.S. and Europe.

Mr. Chatterjee is a member of the USP National Advisory Board, and is the past-chairman of the Golden Gate Chapter of the American Society of Quality. He is the author of Applying Lean Six Sigma in the Pharmaceutical Industry (ISBN: 978-0-566-09204-6) and is a keynote speaker at international conferences. Mr. Chatterjee holds a B.A. in biochemistry and a B.S. in chemical engineering from the University of California at San Diego.