Reimagining Quality Operations In The Life Sciences

This is the third of three articles focusing on an effort to address what appear to be systemic issues across quality departments, informed by a multinational group comprising chief quality officers (CQOs) from pharma, device, animal health, and consumer goods companies.

The first part focused on how quality departments are often perceived negatively in the company, the lack of a common definition of quality, and the 10 things quality departments should stop doing. The second part addressed how to reframe the way we view and discuss quality, how to better engage stakeholders, and an alternate view of how quality can add value to the company. This third and final article in the series will further examine how to achieve cross-functional ownership of quality and the efforts of the CQO team to build quality for the 21st century, including exploring the creation of formal degree programs in quality.

At the annual FDAnews Inspections Summit in late October in Bethesda, MD, Xavier Health director and former head of quality for Merck’s North Carolina facility Marla Phillips shared her research on why pharma quality units are failing to meet their challenge and how they could be redesigned to add more value to the company in a presentation titled “Why Quality Doesn’t Matter.” Phillips has chaired a series of pharmaceutical and medical device conferences cosponsored by the FDA for more than 10 years and has participated in and co-led a number of agency-sponsored initiatives.

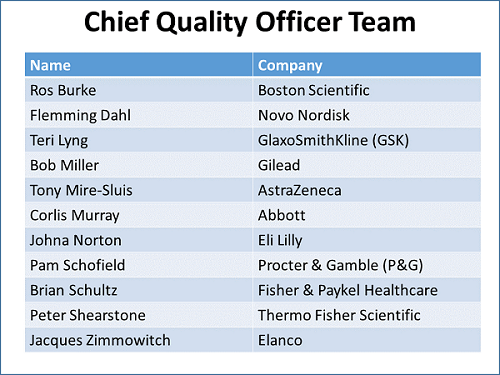

Phillips has formed a team of CQOs — the most-senior quality executives in their companies. The multinational, cross-industry composition of quality leaders is consciously designed to get the most thorough, in-depth thinking and solutions from industries where quality departments operate similarly.

Phillips and her CQO team have discussed among themselves and with cross-functional peers ways in which quality could add more value to the company. These include engaging the various stakeholders, a better understanding of risk to the business of new initiatives, focusing on right-first-time rather than compliance, removing barriers, and understanding the value they bring to investigations and operations.

Phillips noted that the quality organization adds value by bringing a systems approach and critical thinking to investigations and other projects. “If we can support our cross-functional peers enterprise-wide to be able to do this, that is how we are going to be able to mobilize improving the quality effectiveness of our entire company. All of this is going to be grounded in science, data, and awareness of what each stakeholder needs. The key aspect that we will continue to bring in is regulatory intelligence.”

Regulatory intelligence is a systematic process to keep abreast of quality regulations, guidance, enforcement actions, and trends and evaluate those against company policies, standards, and SOPs. The quality organization is pivotal in keeping aware of developments in these areas, interpreting them, and supplying their interpretations such that company management can make informed decisions regarding regulatory agency expectations.

“We have been talking for years about cross-functional quality ownership,” Phillips said. “Originally, we were talking about enterprise-wide quality ownership. But that makes it sound like ‘you do not own this. We are going to try to force you to own it.’ What would be more appealing to our stakeholders is if we talk about quality effectiveness. If we can make it effective, then the system is not going to be shut down and you are not going to be dealing with failures, and you are not going to be stopped in your tracks.”

CQO Team Looking At Formal Quality Education

The CQO team was formed in April, with the first face-to-face sessions in October. The team’s purpose is to “collaborate on leading-edge solutions that drive the future of the industry with and for all stakeholders.” It plans to “redesign the field of quality in a way that maximizes the value of the company for all stakeholders.”

“We identified two opportunities,” Phillips explained. “One is, if we are going to advance the industry we need to redesign the entire field of quality. We want to do it in a way that maximizes the value for the company.”

One of the group’s first actions was to interview their firms’ CEOs and cross-functional business partners and ask a series of questions, including “What should quality stop doing?” (See the first article in the series for the 10 things the quality department should stop doing now.)

The second opportunity centers around a strong interest and passion in developing the next generation of quality professionals who can become leaders in the quality organization of the 21st century in pharma and medical device companies by establishing innovative training curricula and methodologies. “We would like to do that at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We are forming degree options, including minors, majors, and masters,” Phillips said.

Phillips framed the initiative as similar to a cooperative education, where the universities are going to be able to do much on their own, but will need industry involvement. “They might need to have industry personnel teach a class on campus or to participate in online, live learning or on-demand recordings for something that is more foundational, and to be part of mentorships, internships, and coops.”

The CQO team formed a focus group to determine the undergraduate and graduate curriculum needed to feed highly qualified professionals into pharmaceutical and medical device quality organizations. Xavier University has started looking at how it could quickly implement a minor, an easier task than creating a major.

Partnering With The MDIC

The Xavier CQO team is working to further its goal of creating formal quality education by partnering with the Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC).

MDIC is the first-ever public-private partnership created with the sole objective of advancing medical device regulatory science for the benefit of patients. Formed in late 2012, MDIC brings together representatives of the FDA, NIH, CMS, industry, nonprofits, and patient organizations to improve the processes for development, assessment, and review of new medical technologies. It describes its work as “unique and complementary to trade associations such as AdvaMed and MDMA.”

In addition to sharing and leveraging resources, MDIC may help industry to be better equipped to bring safe and effective medical devices to market more quickly and at a lower cost, according to Jeffrey Shuren, M.D., J.D., director of the FDA's Center for Devices and Radiological Health, who was instrumental in getting the initiative started. It is funded in part by the FDA.

MDIC formed a team last summer to focus on quality education. “They reached out to me because I helped lead the FDA’s metric initiative on the device side under MDIC, and because I work at a university,” Phillips explained.

The CQO team is working through a nonprofit, Pathway for Patient Health. “What we want to be able to do is certify any university in the world, saying that it has the appropriate curriculum rigor, faculty credentials, and industry involvement. We would like to be able to create a software platform that allows industry to connect with current students and graduates. I can do that for Xavier through Pathway for Patient Health,” Phillips said.

The CQO team would like to set up a degree program so that “for the first time, a student could intentionally choose a career in quality, instead of it being something that you have never heard of, and once you are in industry you just kind of fall into it.”

Phillips noted that some companies require a person to have a lot of experience before they are allowed to go into quality, “which is phenomenal. But a lot of companies will put them in entry-level auditing positions to allow them to learn by auditing. But they do not know what they are looking at.”

She pointed out that if the degree program can teach students what quality is all about and include instruction in critical thinking and systems thinking, “Then they can go into industry and be ready, and they can cut down the one to three years of training they need to have to understand what GMPs are and be ready to get into action.”

Others in industry and academia who are interested are urged to get involved and give their input. Portions of the CQO team will convene for discussion, input, and networking at the FDA/Xavier PharmaLink pharma conference in March 2019 and at the FDA/Xavier MedCon medical device conference in April/May 2019.

About The Author:

Jerry Chapman is a GMP consultant with nearly 40 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. His experience includes numerous positions in development, manufacturing, and quality at the plant, site, and corporate levels. He designed and implemented a comprehensive “GMP Intelligence” process at Eli Lilly and again as a consultant at a top-five animal health firm. Chapman served as senior editor at International Pharmaceutical Quality for six years and now consults on GMP intelligence and quality knowledge management and is a freelance writer. You can contact him via email, visit his website, or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Jerry Chapman is a GMP consultant with nearly 40 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. His experience includes numerous positions in development, manufacturing, and quality at the plant, site, and corporate levels. He designed and implemented a comprehensive “GMP Intelligence” process at Eli Lilly and again as a consultant at a top-five animal health firm. Chapman served as senior editor at International Pharmaceutical Quality for six years and now consults on GMP intelligence and quality knowledge management and is a freelance writer. You can contact him via email, visit his website, or connect with him on LinkedIn.