Supply Agreements — Does The 'Failure To Supply' Provision Have To Be So Difficult To Negotiate?

By Hal Craig, founder, Trout Creek Consulting, LLC

The failure to supply (FtS) provision in a drug product or drug substance supply agreement — typically ranging from a paragraph to a couple of pages — can be the most hard fought-over “what if” in the agreement and, after price and volume, the section of an agreement with a high potential to fracture a customer-supplier relationship.

On the surface, an FtS provision would seem straightforward to negotiate. In the event of a supply disruption at the drug product CMO, drug substance (API) supplier, or other supplier of a non-readily available raw material, the drug marketer wants its patients to continue receiving their therapies and to experience a minimal impact on its P&L. In an ideal world, the drug marketer would purchase its product from a lead CMO (and perhaps purchase API and other non-readily available raw materials from its respective lead suppliers) and capture economies of scale in doing so. Then, should a supply issue occur with that supplier, the drug marketer would “flip a switch” and begin receiving supplies from a second CMO at reasonable economics. Once the lead CMO is back onstream, the drug marketer would switch back to taking supplies from the lead CMO. Simple, right?

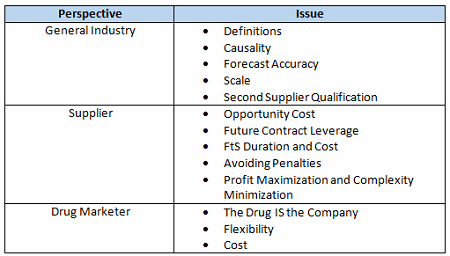

There are several reasons why this isn’t so simple, in part due to the general nature of the drug industry as well as the individual business interests of the drug marketer and its suppliers. Offsetting these issues are the shared goals of helping patients and obtaining a good return on investment and the realization that partners in the supply chain need each other to be successful. Table 1 summarizes the complicating issues that can make compromise difficult without trust. This article, Part 1 of a two-part series, addresses general industry and supplier perspectives.

Table 1: FtS Provision Complicating Issues

General Industry Issues That Complicate FtS Negotiations

Definitions

What is a triggering event for an FtS provision? Is it an order that is 10 days late? More than 30 days late? More than 60 days late? Does the FtS triggering event occur once the order is actually 60 days late or when that the order is anticipated to be over 60 days late? Can either party declare an FtS triggering event on the expectation of a significant supply delay or must both parties agree to the expectation? If at least 50 percent of an order is delivered on time with the remainder promised within 60 days, should this trigger an FtS? Does one late order trigger an FtS or is it two consecutive late orders or three nonconsecutive late orders within a specified timeframe? Is FtS an inability to supply product for six months regardless of whether any orders are forecast for that six-month interval? In other words, is the inability to supply sudden, unplanned, upside demand an FtS triggering event? Is the supplier’s rejection of a validly placed order that is consistent with the forecast both an FtS triggering event and, in certain situations, a material breach of the supply agreement? Does time spent investigating a quality issue count toward the days late? How does slowness on the part of the drug marketer in reviewing batch records, analytical results, validation reports, and deviation reports play into the days-late calculus?

Causality

Is it an FtS provision-triggering event if the supply disruption is caused by something beyond the reasonable control of the supplier and likely to affect alternative suppliers? Examples include an explosion at one of the two chemical plants in the world that supply a reagent that’s several steps back in the supply chain or a surprise labor stoppage at the port where the shipment of a key longer lead time raw material is sitting. If normal seasonal weather struck the area where the suppliers of a typically widely available, routine, raw material are located, and the CMO didn’t adjust its procurement plan based on historical weather-based supply disruptions, would the resulting FtS be something that was within the reasonable control of the CMO? How does the supply agreement handle an FtS based on causality?

Forecast Accuracy

Forecasts of regulatory approval, prescribing rates, impact of competing products, impact of promotional activities, payer coverage, etc., may have a high level of uncertainty during the early commercialization of a new drug product. These factors, combined with the cost and lead time to acquire raw materials, the cost to reserve (if necessary) production capacity and then cancel a campaign, and the expiration date of production-in-anticipation-of-regulatory-approval can create supply shortages.

Scale

Scale issues can involve market, batch, or dosage sizes. Some drug products are chronic therapies with large patient populations. Other drug products are acute therapies or have small patient populations. The global demand for some drug substances could, at least theoretically, be shipped in railcars, while the global demand for other drug substances might theoretically fit into a couple of laptop bags. The point is, for some drug products and drug substances, having a second supplier make one-to-a-few batches per year might represent an insignificant share of global demand; for other drug products and drug substances, an annual report batch might be 25 percent of global demand.

Second Supplier Qualification

It’s an investment of time, money, and human resources to qualify a second supplier, especially a drug product CMO or API supplier. Having at least dual suppliers of key manufacturing processes and raw materials is a prudent strategy to counter supply chain risks such as natural disasters, upside demand, contamination, labor disputes, business disputes, changes in government regulations, and regulatory inspection risk (hopefully inspection risk is low due to good supplier qualification and supply chain monitoring practices). Often, drug products and raw materials are single sourced until commercial drug product demand is such that additional capacity is needed, despite the merits of supply chain risk mitigation earlier in the product life cycle. However, waiting until an FtS occurs before qualifying second sources may cause significant therapeutic and business interruption given the challenges to find and contract with, transfer technology to, produce engineering and validation batches at, and gather stability data at a second CMO.

Issues That Complicate FtS Negotiations From A Supplier’s Perspective

Opportunity Cost

This will typically apply more to drug product and exclusive/custom synthesis drug substance CMOs. These CMOs have invested resources, sometimes at reduced margin, during the process and product development stage in expectation of a more lucrative, longer-term commercial supply agreement. These CMOs may also have invested capital in facility and equipment and dedicated limited manufacturing real estate to a product -- real estate that is idle while that product awaits regulatory approval or is in between production campaigns. CMOs desire to work on projects that favorably “move the needle” of their P&L.

Future Contract Leverage

Once the drug marketer has qualified a second supplier, this can create pressure on the lead supplier to operate with a higher level of planning and efficiency, seek productivity improvements, increase staffing to improve timing, and moderate pricing actions.

FtS Duration And Cost

If there is an FtS provision-triggering event, regardless of whether the FtS was caused by the lead supplier or events beyond its control, how long will the drug marketer take all or a significant amount of its demand from the second supplier? Will it be significantly longer than the time it takes for the lead supplier to fix the cause of the FtS? This is possible given the effort to find, qualify, and bring the second supplier onstream and the volume produced at the second supplier given uncertainty around resolving the cause of the FtS, and the output from the second supplier validation campaign. If the cause of the FtS was action or inaction by the lead supplier, will its post-incident volume (either share or units) eventually return to pre-incident levels or be capped at some level (say 50 percent)? If the cause of the FtS was the lead supplier, will the lead supplier be liable for some or all of the incremental costs incurred by the drug marketer in obtaining alternative supply?

Avoiding Penalties For Items Beyond Reasonable Control

No supplier wants to be penalized for items beyond its control. For CMOs and other suppliers, this can include actions or inactions by the drug marketer, such as providing late or inaccurate forecasts and purchase orders, unwillingness to invest in safety stock inventory (typically long lead or not readily available raw materials and finished goods) to mitigate potential supply issues or as upside demand contingency, and limited drug marketer resources to review and approve documentation. Other items beyond the supplier’s reasonable control can include government approvals (e.g., amount of DEA quota approved vs. amount requested), quality issues with incoming raw materials, natural disasters, and labor stoppages. However, it is a fair question to ask if the supplier is sufficiently managing its own supply chain to anticipate and mitigate some “items beyond reasonable control.” Are some of these items really beyond the control of a supply chain organization following best practices? And even if there are items beyond reasonable control that create an FtS, patients still need their therapies and the drug marketer’s shareholders, creditors, and employees still expect to be paid.

Profit Maximization And Complexity Minimization

In essence, suppliers want the flexibility to pursue higher-value opportunities, respond to short notice upside demand from larger-value customers, minimize overtime, minimize management complexity, minimize liability, and operate in a less constrained way. A supplier would like to operate in a manner that meets its comfort level and goals, with minimal penalty if this creates a hardship for a customer. In short, a supplier wants to run its business in its own way.

Clearly, there are a lot of factors weighing on the FtS negotiation, and the drug marketer hasn’t been heard from yet. Part 2 of this series on the FtS provision discusses the drug marketer’s perspective and a path forward to negotiate a mutually agreeable solution.

About the Author

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.

Disclaimer: This article is intended to provide general information on a particular subject or subjects and is not an exhaustive treatment of such subjects. Accordingly, this article does not constitute legal, accounting, tax, investment, consulting, or other professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that might affect your personal finances or business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. In no event will Trout Creek Consulting, LLC or the author be held liable in any way to the reader or anyone else for any decision or action taken based on this information, or for any direct, indirect, consequential, special, or other damages claimed by the reader or anyone else based on this information.