Addressing 3 Challenges Using The Tablet Press Automatic Weight Control System

By Fred A. Rowley, Solid Dosage Training

In my recent article published by Outsourced Pharma and Pharmaceutical Online, I presented information concerning the operation of an automatic weight control system (AWC) provided by many press manufacturing companies as part of a modern tablet press. After the AWC became part of a tablet press in the late 1970s, it quickly grew from a simple “yes/no” reject mechanism into part of the modern central control panel.

It became an object of concern around 2009 when a plethora of product recalls for oversized tablets in the United States triggered numerous investigations to determine the root cause. As a result, several of the established root causes of over- and underweight tablets were linked back to the AWC. One of the root causes was the incorrect setting of the reject limits used to eliminate tablets out of weight specification.

As more knowledge became available identifying the proven root causes of this serious problem, the frequency of recalls dramatically decreased and the problem was considered under control for nearly a decade. Then, in early 2022 it reappeared. Shortly after that we saw an additional item added to the inspection checklist and the beginning of tighter enforcement by the FDA.

For those not entirely familiar with the AWC operation, the operator first establishes the target weight specified on the product batch record and then proceeds to adjust the thickness control to (hopefully) achieve target tablet thickness and, therefore, target thickness. The control panel will display a corresponding pressure, called the “compressing force,” which is the pressure used to compress the tablet at a specific fill volume of powder using a specific tablet thickness setting at a specific press speed.

At this point, the operator is tasked with setting two additional “tripping points” for the minimum and maximum allowable tablet weights specified on the batch record. This procedure is frequently a semi manual operation where the operator changes the fill volume (tablet weight) upward or downward to the min/max weights specified. Again, we can link these fills (weights) with the compressing forces used to achieve them.

On the batch record, the min/max specification weights are usually a straight 5% range around the target. Therefore, logically, the min/max compressing pressures should also be a straight 5% around the target. And here lies the problem: the theoretical value frequently does not reflect reality. Knowing this, the FDA insists that the min/max weight setpoints should be verified for each batch of each product to better assure that all defective tablets have been isolated from the batch. Doing this is a tedious and time-consuming task and yet it must be performed.

The current industry practice to achieve this goal is not standardized. Some firms attempt to establish these setpoints by manufacturing an “engineering batch” and using these one-time compressing pressures as accepted and proven settings validated for all future production. Other firms attempt to use dry calculated theoretical values in the hope of saving time, effort, and product. Finally, some firms rely on a tablet press manufacturer’s recommended setup procedure, which is almost always based on a dry calculation.

Several difficult situations have emerged from industry reaction to and adoption of this protracted procedure. While companies are required to absorb the cost of the increased sampling to achieve the target weight and the minimum/maximum limits, in addition to delayed start-up times and more frequent aborted start-ups for technical problems, three serious issues have arisen:

1. Before setting the tablet rejection limits, how do I verify that the reject gate is functioning properly? Should this be part of the protocol/SOP used to verify the min/max weight limits? This was a serious issue some years back when numerous recalls were linked to overweight tablets that were not detected and removed from the batch during tablet compression. It was a complex problem, and it was determined that many of the root causes were linked to the failure of the reject mechanism to perform as required. Photo 1 is an example of the problem.

Photo 1: Tablet stuck by the reject mechanism

As a result, strict SOPs and more frequent reject gate verification were instituted industry-wide (hopefully, this includes your company). Assuming that this is not an issue for you, we are now free to address the remaining two concerns.

2. In some situations, we may encounter excessive start-up sampling when manufacturing small batch sizes. As a result, you may exceed the maximum allowable loss and trigger a mandatory investigation. This in turn may also generate some kind of action plan when, in fact, it is unnecessary. And, in addition, there is the cost of the product itself that is lost.

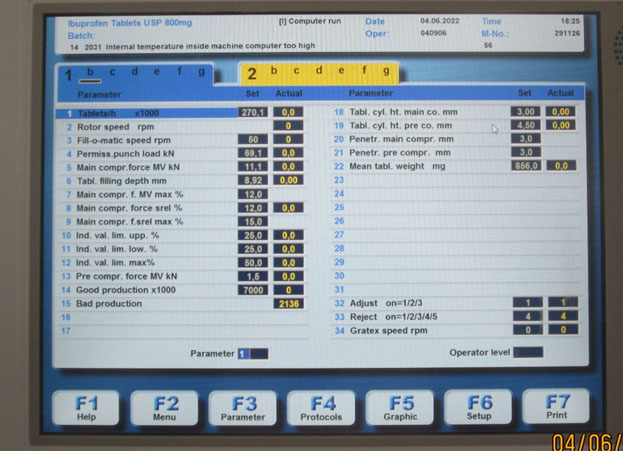

Some generic drug companies have adopted a policy recommended by some tablet press manufacturers — select min/max reject values significantly narrower than would ordinarily be used as a result of a challenge test. Notice fields 10 and 11 in Photo 2 below. In this case, the challenge test results were 34.0 and 36.5, respectively, while the final setting was 25.0.

Photo 2

Essentially, we would be willing to accept a larger loss of product in exchange for a much quicker start-up and the corresponding labor savings.

3. If I am compressing a very small tablet, say 50 mg, the difference in pressures between the target weight and the min/max weight limits stated on the batch record will be very small. This challenge is exacerbated if the tablet press I am using has load cells engineered for larger tablets. The result may be that I am rejecting far more tablets than necessary because the control system is not capable of distinguishing small differences in compressing pressure.

I have seen communications from companies that have adopted the practice of using the signals generated from the pre-compressing station, which has load cells engineered for much smaller pressures, and “tricking” the control system into thinking that this represents the actual pressures used to make the tablet. A more professional approach is to request the individual tablet press manufacturer to provide load cells having the capacity to measure much smaller pressures.

In conclusion, there are several situations that require your validation department to consider alternative approaches to challenging the AWC’s ability to identify and remove out-of-specification tablets in commercial generic tablet manufacturing. Careful application of the procedures I discussed will help achieve this goal.

About The Author:

Fred A. Rowley has more than 40 years’ experience in the pharmaceutical and nutritional supplement industries in manufacturing, technical services, and R&D settings, with particular expertise in solid dosage manufacturing and training. He has knowledge of the granulating, blending, tablet compressing, and film coating processes for more than 800 API drug substances. He is and has been retained as a subject expert by law firms, equipment manufacturers, international pharmaceutical and nutritional supplement companies, and compounding pharmacies, and has lectured at the FDA, the ISPE, and at many colleges of pharmacy around the world. Previously, he has been director, manufacturing technical support, for Watson Laboratories; plant manager, tablets and capsules, Weider Nutrition International; vice president, operations, Arnet Pharmaceuticals; OROS operations manager, Alza Corporation; and bulk solids manager, Syntex FP, Puerto Rico.

Fred A. Rowley has more than 40 years’ experience in the pharmaceutical and nutritional supplement industries in manufacturing, technical services, and R&D settings, with particular expertise in solid dosage manufacturing and training. He has knowledge of the granulating, blending, tablet compressing, and film coating processes for more than 800 API drug substances. He is and has been retained as a subject expert by law firms, equipment manufacturers, international pharmaceutical and nutritional supplement companies, and compounding pharmacies, and has lectured at the FDA, the ISPE, and at many colleges of pharmacy around the world. Previously, he has been director, manufacturing technical support, for Watson Laboratories; plant manager, tablets and capsules, Weider Nutrition International; vice president, operations, Arnet Pharmaceuticals; OROS operations manager, Alza Corporation; and bulk solids manager, Syntex FP, Puerto Rico.