Are You Prepared For The U.S. Enhanced Drug Distribution Security (EDDS) Requirements?

By David Colombo, director, Life Science Advisory, KPMG

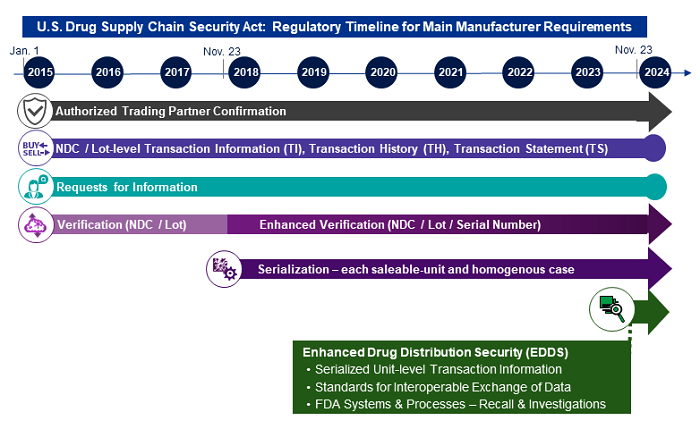

The Drug Quality and Security Act (DQSA) was signed into law almost seven years ago on Nov. 27, 2013. Title II of this Act, known as the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), established a set of requirements and phased compliance dates for prescription drug manufacturers and other participants in the distribution chain to address vulnerabilities in the supply chain and to facilitate the tracing of certain drugs throughout the supply chain. The first major phase of this regulation, which went into effect in 2015, established requirements for manufacturers, repackagers, distributors, and dispensers for the following responsibilities:

Act, known as the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), established a set of requirements and phased compliance dates for prescription drug manufacturers and other participants in the distribution chain to address vulnerabilities in the supply chain and to facilitate the tracing of certain drugs throughout the supply chain. The first major phase of this regulation, which went into effect in 2015, established requirements for manufacturers, repackagers, distributors, and dispensers for the following responsibilities:

- to conduct business solely with other licensed/registered authorized trading partners (ATPs) and

- to electronically transmit product shipment information for each National Drug Code (NDC)/Lot # as it is sold and distributed.

In the second major phase, which spanned 2017-2020, the DSCSA requirements were concentrated on two main areas, the first of which primarily impacted manufacturers and repackagers and the second impacting all ATPs:

- the physical marking of a unique serial number on each saleable unit using a two-dimensional code known as a DataMatrix, with all serial numbers electronically associated to their NDC/Lot #, and

- using this serialized product information to enhance verification processes for events such as restocking of saleable returned product and investigations of potentially suspect or illegitimate product.

These initial requirements of the DSCSA, introduced in a phased manner, were deliberately structured and timed to allow industry to thoughtfully design and implement the required capabilities in preparation for the pinnacle requirement, which goes into effect on Nov. 27, 2023: the implementation of Enhanced Drug Distribution Security (EDDS) capabilities. EDDS will be enabled by the establishment of standards for the interoperable exchange of data, combined with the inclusion of individual serial numbers in the product shipment transaction information transmitted for the NDCs/Lot #s sold and distributed.

Figure 1: High-level timeline of the main DSCSA requirements for manufacturers

What Is EDDS?

Section 582(g)(1) of the DSCSA establishes requirements for the interoperable, electronic tracing of products at the package level. There are multiple requirements, and while some of these are directed at ATPs, including manufacturers, others are directed at both ATPs and the FDA.

Arguably the most significant subsection of Section 582(g)(1) is subsection (B), which calls for the inclusion of the product identifier at the package level in the transaction information (TI) that is electronically provided from the ATP selling product to the ATP purchasing it.

Manufacturers should also play close attention to these other significant requirements of EDDS found in subsections (D) and (E). Subsection (D) calls for the following:

(D) The systems and processes necessary to promptly respond with the transaction information and transaction statement for a product upon a request by the Secretary (or other appropriate Federal or State official) in the event of a recall or for the purposes of investigating a suspect product or an illegitimate product shall be required.

There are a couple of takeaways from this subsection of the regulation:

- The FDA is authorized, and expected under certain circumstances, to formally issue requests to manufacturers and other ATPs in order to obtain transactional information; and

- Manufacturers and other ATPs must be able to promptly respond to such requests in a systematic manner.

Subsection (E) begins by stating:

(E) The systems and processes necessary to promptly facilitate gathering the information necessary to produce the transaction information for each transaction going back to the manufacturer, as applicable, shall be required—

(i) in the event of a request by the Secretary (or other appropriate Federal or State official), on account of a recall or for the purposes of investigating a suspect product or an illegitimate product.

(ii) in the event of a request by an authorized trading partner, in a secure manner that ensures the protection of confidential commercial information and trade secrets, for purpose of investigating a suspect product or assisting the secretary (or other appropriate Federal or State official) with a request described in clause(i).

It is important to recognize that while ATPs should have few, if any, obstacles to being able to promptly gather their own relevant transaction information, some level of oversight and coordination will be required in order to compile all of the relevant transaction information across all impacted ATPs.

Why Oversight Is Necessary

Let’s take the scenario where a manufacturer, in conjunction with the FDA, issues a Class I product recall (the most severe), indicating the National Drug Code (NDC) and lot number being recalled. Because a single lot number can be transacted upon by multiple ATPs, and because all of those ATPs may not have direct relationships with one another, a mechanism must be put into place such that a complete and comprehensive gathering of relevant data across all impacted ATPs can be achieved. One can infer from this portion of the DSCSA that the FDA, specifically the Office of Drug Security, Integrity, and Response (ODSIR), will play the pivotal role of overseeing the end-to-end process of formally requesting and gathering relevant data from impacted ATPs in support of events such as product recalls. This includes collaborating with industry to define the standards for transmitting this information in a systematic way and to define the overall process for managing requests, responses, analyses, and related communications.

The Use Of Aggregation And Inference In The Distribution Channel

In order to meet the requirements of 582(g)(1)(B), manufacturers, their contracted third-party logistics providers (3PLs), and their selected distributors, who execute high-volume/high-velocity product shipments for individual product SKUs, will require the following capabilities:

- Aggregation: The electronic linkage of serial numbers within packaging hierarchies, e.g., unit‑to‑case, case‑to‑pallet.

- Inference: The ability to transact on the entire contents of a container (case, pallet, tote, or other aggregate of individual packages), using the outermost container serial number, combined with the aggregation data, thereby avoiding the need to open the container to scan each individually serialized package.

Aggregation and inference should be thought of as interdependent capabilities that will be needed in order to efficiently associate the serial numbers being shipped, with minimal disruption of product packaging/security (e.g., sealed homogeneous cases of product; stretch-wrapped or banded pallets).

A complete solution requires timely and accurate changes to aggregation information throughout various distribution operations and exceptions in order to leverage inference during outbound delivery serial number association.

Aggregation data errors by association will result in inference errors, which by association will result in erroneous transaction information files provided to trading partners, requiring time-consuming manual intervention to investigate and systematically correct.

Inference tools must be robust enough so as to not overly constrain the picking/packing rates expected, i.e., the solution architecture and design between the serial number repository and the warehouse management system (WMS) and any automated picking solutions integrated with the WMS must support timely processing and recording of transactional data; otherwise, it will introduce a new bottleneck in the distribution center.

When should inference be used? It is highly recommended that manufacturers determine for which individual SKUs (i.e., an individual product NDC) it makes sense to maintain the aggregation data established during the packaging operation and extend it into the distribution operation, in order to leverage inference capabilities. Lower volume/lower velocity products that are often supplied in quantities of less than a single full case are poor candidates for leveraging inference. This can be concluded when the cost/effort to maintain accurate aggregation data is not rewarded (offset) through sufficiently reduced cost/effort saved during the outbound picking/packing process. In other words, it is “less painful” to individually scan serialized units for some SKUs than to completely and constantly maintain aggregated data for every case/pallet of that product. Regardless of outbound distribution volume, there are always benefits to aggregating serialized product in the packaging operation for overall control, accountability, and end-of-lot reconciliation purposes. The assessment recommended here is to measure the marginal utility expected through higher productivity and efficiency in order to determine where/when to deploy inference as a tool.

ERP and WMS solutions need to be flexible enough to accommodate the reality that not all SKUs will exceed the cost/benefit threshold to use inference, and system functionality may need to vary accordingly for some transactional processes. New configuration/product characteristics at the SKU level are needed in order to drive the functionality required. By taking this approach, only the appropriate products and product transaction types will contain the necessary systematic user prompts, data collection, and subsequent processing for various inventory-related transactions.

Clearly Defined Organizational Roles And Responsibilities: It’s A Team Sport

In addition to system functionality to support inventory transactions in the distribution center operation, organizations need to invest time to enhance processes that either impact or are impacted by serialization and product traceability. Of equal importance, clear delineation, articulation, and understanding of requirements and expectations across all impacted roles are critical. This includes the role’s duties/responsibilities, boundaries for decision-making authorization, limits on access to transactional data, allowances for providing data, and overall internal and external interactions/communications. Clarity in operational governance will be of vital importance for manufacturers to avoid confusion when various supply chain events or interactions with external parties, including regulators, occur.

For example, imagine a scenario in which the FDA needs to make an inquiry to the manufacturer related to distribution transactional history and activity for specific product SKUs across certain trading partner(s).

- What functional role is on point to monitor activity/receive the inquiry? Are response time requirements understood in order to establish due date/time?

- Does this same role execute the assessment and response, or is coordination with other roles internally needed? (The latter is typically the case as a normal division of duties.)

- What reviews and approvals of information and accompanying communication that are intended to be shared externally are required to be conducted within your organization?

Failure to define the operational parameters and protocols may result in failures when called upon to respond to regulatory or trading partner inquiries or in the overall execution of system processes. It is recommended that manufacturers leverage a well-configured systemic tool for electronic capture of all requests, their associated assessments, the supporting data retrieved, communications, and close-out. Such an approach will also support DSCSA compliance requirements that call for storage/maintenance of product verification requests and product investigations.

The Silver Lining

The good news here is that the EDDS requirements of DSCSA present an opportunity for organizations to realize improvements while meeting the compliance mandates:

- Order quality, completeness, and accuracy can be achieved through integration of picking solutions with serialized codes, aggregation, and inference. Conventional WMS solutions that only confirm and record item/lot using bar coded bin locations or pallet-level “license plates” to help verify the right product is being picked should evolve to leverage the item, lot, and expiry data elements in the serialized codes printed onto the packaging at the unit and case levels. Expired product or product with limited months of remaining shelf life can be flagged during the picking/packing process if those with a longer shelf life should be supplied. This can reduce unnecessary product returns, which carry additional transaction costs and potential for revenue loss if credit applied is greater than it should be.

- Integration of suspect/illegitimate product investigations with product complaints and CAPA can be pursued and include obtaining serial numbers in addition to the NDC/Lot# data. Furthermore, a detailed assessment of the historical distribution events of that NDC/Lot/Serial # can be conducted. This could potentially identify factors relevant in that serialized unit’s storage and distribution profile, including information such as elapsed time from originating shipment from a manufacturer. Capturing and leveraging this information provides a forensic profile of sorts that may offer insights into the issue’s potential root causes or other contributing factors.

- Product quality – Manufacturers should work with their 3PLs and distributors to eliminate, or at least minimize, product returns where possible. Each time a drug product is returned, restocked, and resold it is vulnerable to events that might negatively impact product quality. Verification of saleable returns should not only confirm legitimacy but should also not allow repeated returns/restocks of the same serialized unit and possibly trigger other follow-up investigation and communications depending on product, customer, or frequency of occurrence.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that the prescription drug product traceability and reporting requirements at the individual, serialized unit-level will require considerable planning, assessment, decision-making, change control, and execution. Manufacturers need to proceed quickly but thoughtfully and should approach this upcoming era of serialized product traceability holistically by expanding their objectives beyond achieving and maintaining compliance.

Organizations that leverage their new capabilities that originated from compliance efforts to other use cases and applications will be well positioned to “raise the game” in areas of product distribution quality; data accuracy and completeness; thorough, timely, and documented responses to inquiries; and overall organizational process design and governance.

About The Author:

David Colombo is a director within KPMG’s Life Sciences Advisory Practice, with over 25 years of experience supporting supply chain execution processes at a large global pharmaceutical company. Prior to joining KPMG, he spent six years dedicated to product coding, serialization, and traceability implementing solutions in Turkey, China, South Korea, the EU, and the U.S. You can reach him at davidcolombo@kpmg.com or connect with him via LinkedIn.

David Colombo is a director within KPMG’s Life Sciences Advisory Practice, with over 25 years of experience supporting supply chain execution processes at a large global pharmaceutical company. Prior to joining KPMG, he spent six years dedicated to product coding, serialization, and traceability implementing solutions in Turkey, China, South Korea, the EU, and the U.S. You can reach him at davidcolombo@kpmg.com or connect with him via LinkedIn.