Environmental Risks & The Life Science Supply Chain: Lessons Learned From Hurricane Maria

By Carla Reed, president, New Creed LLC

The hurricane season of 2017 will be remembered as one of the worst, with some of the strongest tropical cyclones ever witnessed creating havoc in the Atlantic basin.

The financial impact of these storms is still being measured, but of the more obvious outcomes are:

- major disruptions to large U.S. ports (Port of Houston was out of commission for over a week after Harvey.)

- millions of people without power for days

- billions of dollars of crop damage ($2.5 billion in Florida after Irma)

- major delays and disruptions in the movement of raw materials and products with impacts across the world.

Looking at the past season from the perspective of supply chain risk — and specifically risks that have impacted the life sciences supply chain — there are many lessons to be learned.

Puerto Rico: A Tiny Island With A Huge Life Sciences Impact Brought To Its Knees

A case in point is the impact of Hurricane Maria on Puerto Rico — a critical link in many life sciences-related supply chains. The legacy of tax incentives in the 1970s (phased out in 2006) is a concentration of life sciences companies on this tiny Caribbean island. Many global companies have operations in Puerto Rico, some of which are single-source locations for raw materials, components, and finished products.

Consider a few data points:

- More than 25 percent of pharmaceuticals exported from the U.S. are produced in Puerto Rico — with more than 50 plants and distribution centers supporting the flow of starting materials and work-in-process and finished products. Pharmaceuticals represented 72 percent of Puerto Rico's 2016 exports, valued at $14.5 billion, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- The sector employs about 90,000 workers.

- Puerto Rico is a distribution point for other parts of the Caribbean.

Hurricane season is a known factor in Puerto Rico, and companies there have built it into their business continuity plans. Stockpiles of generator fuel, backup UPS (uninterrupted power supply) emergency staffing plans, and other mitigation strategies are a part of doing business in Puerto Rico. However, no one expected a hurricane of this proportion would create the potential long-term damage Maria did. Many months later, the aftermath is still being evaluated — millions of dollars of property damage and the impact to the overall infrastructure of Puerto Rico. There are growing concerns related to the ability of manufacturing sites to recover to the extent where they are able to resume production and rebuild their inventory buffers. Despite assurances from large pharmaceutical companies that have operations in Puerto Rico that their contingency plans and redundant network designs will ensure supply, there are concerns about potential product shortages. The impact of this on the life sciences supply network should not be underestimated and is already being felt in many other parts of the world.

In addition to the damage to production and distribution facilities, the destruction of roads and other core infrastructures creates logistical challenges. Getting fuel to the backup generators providing power to manufacturing sites, storage locations, and distribution operations is a major challenge for the foreseeable future. Communication is also a challenge — a large percentage of communication is currently reliant on satellite telephones, as the majority of cellular phones are still not working.

Another factor critical to the recovery of production capacity is the impact on the local workforce. Homes have been destroyed, electricity and running water are things of the past, and transportation to the workplace is a major challenge. For those able to put in the time and effort to contribute in production roles, there are other considerations. Sterile manufacturing depends on uncompromised water sources, which cannot be guaranteed when supply lines have been damaged. And the impact of disruption to air conditioning — potential growth of mold and other organisms that flourish in hot, humid locations — is potentially catastrophic. Once sterile manufacturing locations have been compromised, restoring them is time consuming, costly, and potentially impossible.

Added to these woes is the issue of financial constraints — the island is effectively bankrupt, and costs to rebuild the infrastructure are still being calculated. The complications are numerous — but the end result is the same: reduction in capacity for life sciences production.

The FDA is supporting the remediation activities of the life sciences community, allowing the import of critical supplies of items like saline and intravenous (IV) fluids. Puerto Rico was one of the major production locations for this staple in all medical facilities. Other global authorities are supporting the efforts of life sciences entities affected by shortages of materials and product. As pharmaceutical and other life sciences companies develop strategies for recovery from the impact of Hurricane Maria, it provides an excellent case for global disaster preparedness across all critical supply chains.

The disaster in Puerto Rico put a spotlight on some of the critical medical products that depend on the manufacturing sites there to meet patient needs. But other items may be affected by shortages. Companies are not required by the FDA (and other authorities) to disclose where products are manufactured. Therefore, it is hard to predict which other items are at risk of shortages.

Winter Storm Shuts Down Transportation Of Critical Supplies

Close on the heels of the tropical storm season was the winter storm that brought in the New Year along the East coast of the U.S. Winter storm Humphrey, the “bomb cyclone,” brought freezing gale-force winds which swept up the coastline, while snow and ice closed roads and airports and brought whole areas to a standstill. The impact of this storm has been felt from Florida to Vermont. The domino effect was widespread, affecting travel and transportation along the coast and into the interior. Hundreds of flights were cancelled, impacting passengers and delaying shipments moved by a combination of air and ground transport between major centers, many of which are key sources of supply and distribution for life sciences products. There is a concentration of pharmaceutical facilities in New Jersey, New York, and New England, and these areas are home to many facilities engaged in research and development for biotech and gene therapy. Critical supplies of time- and temperature-sensitive human tissues collected in areas not affected by the weather and destined for clinical sites in the Northeast are just one example of materials that could degrade due to variations in temperature and delays in transit. This highlights the need to understand potential hazards for goods in transit and build mitigation and remediation plans as part of an overall supply chain strategy.

Every Link In Your Supply Chain Is A Point Of Potential Failure

How many companies are unaware of the location of their primary suppliers? And assuming the location of primary suppliers is known, how well-known are the related tier-two suppliers and the extended network of supply locations that support a specific product?

Over the past decades, many companies have extended their supply chain operations to new locations, either directly or through outsourcing to contract research, development, manufacturing, and distribution partners. Supply chains are networks of interconnected operations and support services, a failure to any of which could have a negative impact on other links in the chain. Understanding these interdependencies is critical — down to defining each process step from acquisition of the source material to the moment a finished product is available for patient consumption.

Learning from these two natural disasters, supply chain dependencies should be evaluated from end to end, developing a holistic process understanding. Each of the related supply chain elements should be reviewed and mapped out with dependencies, constraints, and risk factors highlighted. In order to ensure all aspects of material storage, packaging, shipping, and related regulatory compliance are taken into account, a cross-functional team should be formed to engage in the risk analysis and development of the mitigation and remediation plan.

Detailed process flows with related inputs, outputs, and outcomes should be developed, identifying all participants that impact the ability of the enterprise to operate in an optimal manner. Entities should include the suppliers of raw materials, starting materials, API, manufacturing, and packaging components — literally any organization that contributes to the success of the overall supply chain. In addition, the logistics functions between the links in the chain should be defined, identifying modes of transportation, service providers, and requirements for product protection, time, and temperature monitoring. High-risk transportation routes should be identified and evaluated to create opportunities to reduce trans-shipment, damage, delays, or any other factor that could impact the ability to move materials and product across the chain of custody.

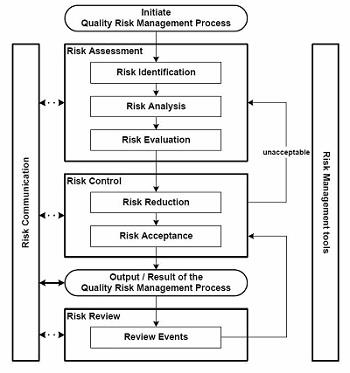

This can then be assessed using accepted standards and guidelines for quality risk management for cGXP. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Defining the end-to-end supply chain with related participants, roles, and responsibilities provides a baseline for a broad and shallow as well as a narrow and deep risk assessment. The team should evaluate each link in the chain, taking into account geopolitical risk, weather-related hazards, and operational and regulatory risk factors. Considerations related to the impact of shortages of raw materials, transportation delays, and disruptions — all elements of the overall supply chain from design to distribution (including reverse logistics) — should be considered. Risk assessments should also take into account all factors that could compromise the quality, integrity, and efficacy of medicinal products. These risks can then be grouped into categories with related cause/effect and likelihood/impact. By a process of elimination, it will then be possible to isolate key risk factors and develop a remediation strategy with associated action plan.

Natural disasters are a way of life. But information is power that can be acted upon to reduce the impact of disruptions.

About The Author:

Carla Reed is a supply chain professional with more than 20 years of experience in supplier engagement, manufacturing, emerging market development, outsourcing, global trade, regulatory compliance, storage, and distribution. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at carla@newcreed.com.

Carla Reed is a supply chain professional with more than 20 years of experience in supplier engagement, manufacturing, emerging market development, outsourcing, global trade, regulatory compliance, storage, and distribution. Her firm, New Creed LLC, provides change leadership to facilitate sustainable solutions, providing hands-on experience in all aspects of supply chain operations. You can email her at carla@newcreed.com.