Evaluating the Effectiveness of cGMP Training

David E. Jones, GMP Institute

Contents

Introduction

Evaluation of Training Is Nothing New

Why Is Effective Training Misunderstood?

Measurement: One Key to Effective Training

What Did the Participant Think About the Training?

What Did the Participant Learn?

Is the Knowledge Being Applied to the Task?

What Was the Company Benefit of Training?

Conclusion

About the Author

References

Introduction (Back to Top)

As we move into a new century, it's an appropriate time to consider what "effective training" means to your company today and what it should mean in the near future. Increased competition and decreased margins are sometimes responsible for less training, when better training may be the missing component in much needed performance gains.

If a production or assembly process doesn't produce the desired quality product on a consistent basis, the author contends that most companies would change the process. If a piece of equipment doesn't fulfill its intended purpose on a consistent basis, it would likely be repaired or replaced. However, if a training program fails to bring about a positive change in employee skills, it's less likely that any change will take place in the training.

Why the difference? The reason is often the lack of evaluation.

Companies evaluate components, processes, raw materials, and the product both at in-process and final production steps. Companies less frequently evaluate their training programs. Fortunately, it's not difficult with proper planning. This article suggests some ways to evaluate the effectiveness of training, e.g., verifying that training has accomplished its intended goals before employees engage in their tasks instead of discovering through costly errors that they have not been qualified through training.

Evaluation of Training Is Nothing New (Back to Top)

Consider the following statements on training: "Training is a dynamic process to assure that personnel are capable of performing their assigned functions. CGMP regulations contain only general expectations, and no FDA guideline regarding training has been issued…. A pharmaceutical (or medical device, ed.) firm should be able to show that its training program consistently meets its training goals as purported and that each trainee completing an instructional module has acquired the competencies as purported."

"The proper application of sound principles of instructional design should help firms overcome GMP deficiencies regarding training and personnel qualification. For example, principles of mastery learning, competency-based instruction, performance objectives, a systems approach to instructional design, and the evaluation of instruction as well as the instructional program should help ensure meaningful, relevant training and appropriate, effective instruction. Review of training should be included in the firm's program for managing change" (Ref. 1).

These comments clearly identify the goals of effective training as well as the expectations of the Food and Drug Administration, but the expectation is not a new one, and the article (derived from a speech) was written almost a decade ago. The key points, however, are just as timely today as when the comments were first delivered.

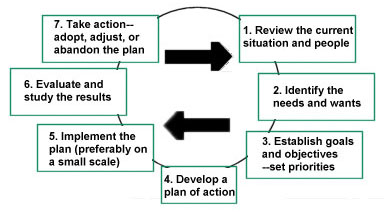

The GMP Institute offers an on-site GMP training course that emphasizes the seven steps of GMP compliance.

A review of a 40-page consent decree issued in 1998 (Ref. 2) underscores FDA's expectation of evaluation of training in the subject firm. The consent decree outlines in relatively specific terms what the FDA expects of the firm in the establishment of controls and the monitoring of same. Ten percent of the consent decree deals with training. Not only is the firm expected to train all personnel who manufacture the products of the subject firm, the firm is held accountable for devising a method to measure the effectiveness of its training. Further, any employee of the firm who does not demonstrate the knowledge and skill to perform his/her job correctly must be removed from that task until remedial training enables them to demonstrate adequate knowledge and skill. (Evaluation is required to implement the provisions of this decree).

The cGMP regulations for the manufacture of drugs or medical devices are industry specific, but each is still subject to interpretation, so a single regulation will cover all firms and various products within those industries. Periodically, firms have asked if the FDA will publish a guidance document for training. To date, that answer has consistently been "No." In responding to such inquiries, FDA has stated in various workshops that the regulations speak clearly and concisely to the need to train personnel. It doesn't take much interpretation to determine that the FDA means "effective training."

Why Is Effective Training Misunderstood? (Back to Top)

Before exploring the evaluation of training, it's worthwhile to make a comment about less-than-effective training. Training, as used in this article, means any classroom, shop floor group, or one-on-one scenarios in which a person, often a supervisor or line leader, attempts to impart job or task information to one or more people. It may involve a specific task technique for safety or quality, documentation, or following the steps of a particular operating procedure.

Poor, inadequate, and ineffective training has an insidious way of being perpetuated if those who do the training and those who receive the training have never been exposed to effective training. The characteristics of poor training start with vague or completely missing objectives, i.e. the expected result of the training. The training itself may be poorly designed and poorly presented. Finally, it's unlikely that the impact of training, e.g., measuring the results, will be determined.

These misguided attempts might be captured in this statement: "After all, as long as a company can produce training records upon request of an FDA investigator, the company has met its regulatory obligation for training, right?" Wrong! Some training records are virtually valueless because they only record failed attempts at imparting the information required to perform tasks correctly and consistently. This hardly complies with FDA's expectation that employees are qualified through training.

Accompanying the misguided concept that anything that even remotely resembles training will qualify as "training" is the absence of any "instructional objectives," i.e., what does the Company want the employee to be able to do after the training. To be even more specific, one can further qualify the conditions and the output expected of a properly trained employee. When instructional objectives are known and stated, training then has specific objectives, and the outcome of training is measurable.

Writing clear and specific objectives is a challenging task, but it is the logical and necessary first step to effective training. While errors may be one source of identifying training objectives, this is a remedial approach. A more proactive approach is to break each job or task into its critical steps to ensure that each step is adequately addressed in the training.

Even in the face of substantial data, the author still finds that training—effective training—is still one of the last options to be undertaken. It's not unlike the time-worn phrase, "When all else fails, read the instructions." Sadly, when all else fails, some companies finally and begrudgingly engage in employee training. This is hardly the "proactive" approach expected by basic good management principles and by cGMP.

Measurement: One Key to Effective Training (Back to Top)

Much has been written on the evaluation of training and this writer, like many others, refers to the work by Donald Kirkpatrick in which he described many years ago a useful four-level evaluation process: Reaction, Learning, Behavior, and Results (Ref. 3). Some will dispute the utility of Kirkpatrick's model or challenge it because of its simplicity. Others agree with the relatively simple approach and find that it provides useful insight into the impact of training. The reader can determine what evaluation steps will likely work in his or her company, how evaluation of training can improve the training process and, more importantly, the outcome of training.

Here are the typical steps that can enable one to evaluate and then improve a training program or a module with a series of training modules. Evaluation is closely tied to the other steps that should be undertaken to plan, implement, pilot, evaluate, conduct, and then evaluate a training program.

What Did the Participant Think About the Training? (Back to Top)

Training literature often repeats that the "participant learns what he/she wants to learn," and if participants react negatively to a training program, it's not very likely that many attending a training session will take much of value from it. Measure or evaluate what the participant thinks about the program with "user friendly" evaluation forms such as the one suggested in Figure 1. Remember, this doesn't indicate what the participant has learned; it merely tells the trainer what the participant liked and didn't like. It's possible to entertain participants and obtain high scores on the evaluation while imparting little useful job knowledge.

If one collects such data, one should be prepared to react to it. When participants learn that their comments have been read and taken seriously—and positive changes in the training would be the evidence to support this—participants then have some ownership of outcome. If comments are ignored, participants will be less likely to share their input.

What Did the Participant Learn? (Back to Top)

Can one use written examinations to measure the transfer of knowledge in device and pharmaceutical training? The answer is a qualified, "Yes." While measuring knowledge is important, it is more important to measure the correct application of the knowledge, which may be defined as skill. The knowledge should include the reasons for the various steps in the manufacturing or testing process because "telling why" will lead to higher conformance with the specified procedure or work instruction.

Most readers will have been exposed to the typical teaching and measurement process in either high school or college, where a student's knowledge—acquired in the classroom and through additional study—is tested by way of a written examination. This is a simple but usually effective method of measuring knowledge so long as the examination is fairly correlated to the material assigned and the questions are formulated at an appropriate level of difficulty. In preparing such an examination, the instructor must pose questions in a clear and unambiguous manner and be certain that the questions are an accurate reflection of the key points in the subject matter presented. The instructor must strive to ensure that the examination measures knowledge and not literacy. This is especially important in a diverse classroom or company.

If a written examination is used, there are advantages to using questions with multiple choice answers. They are more "user friendly," answers are standardized, and the examinations are easier to grade. When a particular question is frequently answered incorrectly, the trainer should review the wording of the question and answers for accuracy and clarity and review the training material to ensure that the topic was covered adequately and correctly.

Here are a couple of example questions that might be relevant:

Applying the correct torque to a fastener in assembling our medical device is important because:

a. Over-tightening a fastener can damage or break the assembly.

b. Under tightening a fastener can allow the assembly to malfunction.

c. Both "a" and "b".

d. Neither answer is correct.

When making, GMP Amine, the blend time for raw materials in the Acme Blender:

a. Is a broad guideline subject to individual employee interpretation.

b. Can be ignored so long as the material is blended for approximately 30 minutes.

c. If performed incorrectly, the mistake can be caught by QC testing.

d. Should be followed exactly to avoid both under-blending and over-blending, either of which can result in a batch that is not homogeneous.

Note: A passing score on a written examination is not the most accurate measurement of a training's impact, because measurement of knowledge is but one facet of training. It's the consistent application of the correct knowledge that meets the expectation of the cGMP regulations and corporate production goals.

Is the Knowledge Being Applied to the Task? (Back to Top)

A passing score on a written examination verifies that the training session successfully related the desired information. More importantly, however, is the knowledge being applied to the job. The logical analogy is the "knowledge" captured in a written SOP as compared to the actual practices in performing the task.

If production errors prompted the training session, are errors reduced after the training session? Be careful to quantify the types of errors previously made as compared to any errors made after the training. A better question might be: Are errors of the types covered in training reduced after training? And, if errors still plague production, does training need to be directed at the prevention of other types of errors?

If productivity is charted and shared with employees, improvement in productivity should be evident after training, provided that all other factors remain constant. Output, number of correctly filled orders, orders shipped on time, and profit are the outcomes that managers want to see as a result of training. These improvements are realistic expectations, because training is undertaken for specific reasons.

Things get a bit more complicated when one considers practice. If employees "know" the correct procedure and aren't following it, the answer may not lie in training, but in supervision or management. The role of training is to equip employees to perform tasks correctly on a consistent basis. This may not be achieved if their training is superseded by supervisory or management intervention, which is contrary to both SOPs and to stated training objectives. Does this suggest that both managers and supervisors should receive training that is appropriate and related to their role in manufacturing and testing products?

That answer is "yes."

Even under ideal working conditions, knowledge and adherence to established practices can erode over time without proper reinforcement. This is addressed in the cGMP regulations by the expectation that training must be done with sufficient frequency.

What Was the Company Benefit of Training? (Back to Top)

Or, to use Kirkpatrick's term, "what are the results" of the training? In a cGMP environment, was there:

- A reduction in manufacturing errors?

- Higher output of correctly manufactured product or device?

- Fewer documentation mistakes?

- Increased awareness—as suggested by questions before mistakes are made?

- Or, getting back to the design of the training program, were original objectives satisfied?

- What types of improvements have been suggested as a result of the training?

- Was change control followed correctly?

- Was "training" included as part of change control?

Does management realize some tangible benefit from the training? Does this benefit translate into higher profit, better utilization of personnel and equipment, improved customer satisfaction, new business opportunities, or fewer observations on customer audits? Managers expect some ROI on training and are not likely to support "training for the sake of training." Evaluation is a tool to help both managers and trainers obtain the maximum benefit from the training undertaken.

In some industries, measuring the "results" of training can be very difficult below the profit and loss statement, but in medical device and pharmaceutical manufacturing companies, the extensive records that are routinely kept make measurement of results through record review a more realistic task. This is especially true when it comes to errors in documentation and manufacturing or assembly steps. A drop in deviation reports—and the time required to investigate and document the deviations—may be a significant outcome following training. A reduction in packaging or labeling errors quickly translates into savings.

Conclusion (Back to Top)

Do errors just happen? No, they are caused. When training effectively addresses the reasons for errors to prevent them, a firm is then deriving both compliance and productivity benefits from its training efforts.

Training is still the primary means through which employees are qualified to perform their assigned tasks. Like other factors in the manufacturing and testing processes, training should also be evaluated. How can it be improved if it isn't evaluated? If asked by an auditor to verify the effectiveness of a training program or ongoing training, a firm should be able to offer some evidence that the training is effective. Aside from the inquiry from an auditor, a firm should expect both knowledge transfer and appropriate behavior change from the time and money that is expended for the training of employees. These can be verified through evaluation.

About the Author (Back to Top)

As an an enthusiastic and knowledgeable proponent of GMP, David Jones has extensive experience in the ethical and OTC pharmaceutical industry with American Home Products Corp. and A.H. Robins Co. (responsible for Eurand International SpA, Eurand America Inc., Viobin/SPL and Agri-Bio Corp). Jones has held positions in marketing, research administration, project management, business development and general management. He holds a B.S. in pharmacy and a masters degree in business.

As an an enthusiastic and knowledgeable proponent of GMP, David Jones has extensive experience in the ethical and OTC pharmaceutical industry with American Home Products Corp. and A.H. Robins Co. (responsible for Eurand International SpA, Eurand America Inc., Viobin/SPL and Agri-Bio Corp). Jones has held positions in marketing, research administration, project management, business development and general management. He holds a B.S. in pharmacy and a masters degree in business.

- Levchuk, J.W., "Training for GMPs: A Commentary," Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, Maryland. (These comments were delivered to the Parenteral Drug Association at its program, "Training for the 90s," Arlington, VA., Sept. 1990).

- U.S. District Court for Central District of CA, USA vs. Alpha Therapeutic Corp., Consent Decree of Permanent Injunction, Jan. 1, 1998, XIV Training: E, pp. 11.

- Kirkpatrick, D., "Great Ideas Revisited," Training & Development, Vol. 50: No. 1, Jan. 1996, pp 54-57.

For more information: David Jones, GMP Institute, 15607 Hampton Arbor Court, Chesterfield, VA 23832-1969. Tel: 804-639-6655. Fax: 804-639-6655.

Terri Kulesa, Institute of Validation Technology, 200 Business Park Way, Suite F, Royal Palm Beach, Florida 33411. Tel: 561-790-2025. Fax: 561-790-2065.