First In Line: FDA Vs. EMA Biopharma Approval Times

By Brendan Wang and Christian Thienel, Back Bay Life Science Advisors

The vast majority of biopharma companies place the most emphasis on the U.S. market as the pillar of their business case and commercial strategy. The conventional wisdom is that price potential is significantly larger in the U.S. and the lack of time-intensive healthcare technology assessment (HTA) processes like those seen in Europe are the key drivers of this phenomenon. However, often lost in this discussion is whether the regulatory agencies themselves have a major impact — namely whether there is any difference in approval timelines between the FDA and EMA.

In the last five years, more than 200 new therapeutics have been approved by the FDA, including NDAs and biologics license applications (BLAs). We were curious to understand a few key questions about FDA approved products, namely:

- How does FDA approval date compare to EMA market authorization date?

- Are there any patterns regarding which products are approved first by the FDA and then by the EMA, and vice versa?

- What implication does this have for biopharma companies as they consider launch sequencing?

By examining these key questions, we ultimately characterize how frequently the products received U.S. approval ahead of the EU in terms of introduction of novel therapeutics. Our initial hypothesis was that most products are approved first by the FDA and then by the EMA.

Crunching The Numbers — Which Agency Issues Approvals Earliest?

From 2015 to 2019, the FDA approved 220 new drug filings, either as NDAs or BLAs. Of these, 123 are not yet approved by the EMA and have been excluded from analysis for comparison purposes, leaving a total of 97 approvals issued by both the FDA and EMA from 2015 to 2019.

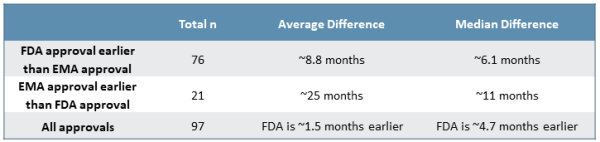

Comparing FDA approval date to EMA market authorization date, the FDA generally issues approvals more quickly than the EMA (see Figure 1). Approximately 78% of NDAs/BLAs receive marketing authorization in the U.S. prior to the EU, whereas the remaining 22% of NDAs/BLAs are approved in the EU prior to the U.S. Homing in on the drugs approved first by the FDA, there is a median difference of approximately six months between the two approvals, while drugs approved by the EMA prior to being approved by the FDA see a median difference of about 11 months. Though uncommon, we later investigate specific cases of EMA approval prior to FDA approval to better understand the dynamics and context surrounding these examples.

Figure 1

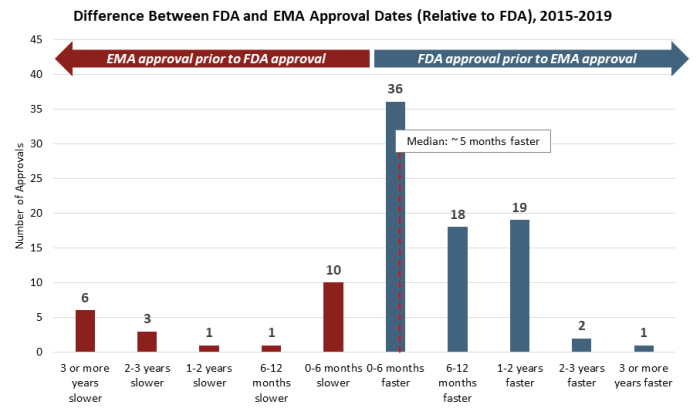

While many variables affect individual decisions by each agency, there is clear trend to earlier FDA approvals by a meaningful margin. This is made increasingly clear when considering the distribution of approval delta between the FDA and EMA (see Figure 2). Roughly 75% of approvals from 2015 to 2019 saw earlier decisions from the FDA on the order of a few months to two years faster, with roughly half of those decisions falling in either the “six to 12 months faster” or the “one to two years faster” groups. Additionally, while outliers exist on both ends of the spectrum, there are several unusual cases where the EMA issued an earlier approval than the FDA, which strongly impact median approval differences for approvals issued first by the EMA.

Figure 2

This trend is also consistent across a number of data cuts and categorizations. There is no discernible difference in approval dates between NDAs and BLAs, though it is notable that there are no cases where BLA approvals have been issued by the EMA more than six months earlier than by the FDA, with the vast majority of examples showing earlier FDA approvals. There is also no discernible difference by route of administration of the active ingredient, as approvals for oral and injectable therapies mirror those of the broader data set. Finally, this trend has also been consistent over time, with a similar distribution of approval date differences in each year from 2015 to 2019.

The EMA Only Beats The FDA Under Atypical Circumstances

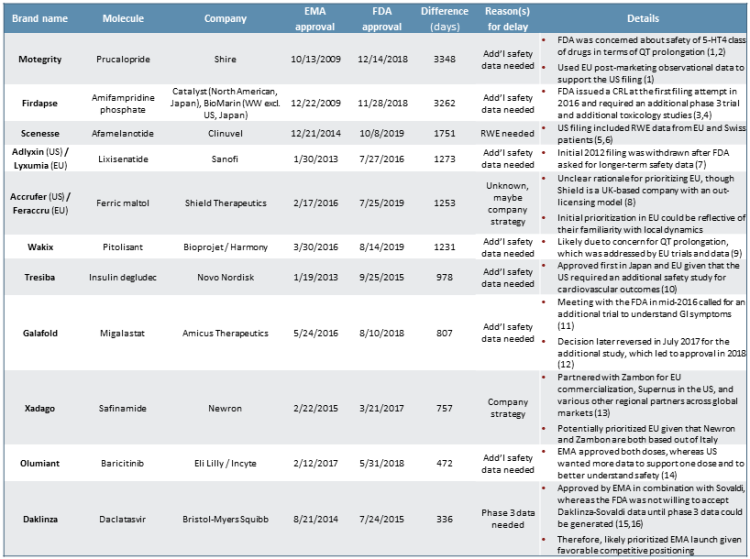

We next explore the outlier cases in which an EMA approval comes before an FDA approval, which has occurred in roughly 22% of drug launches in both regions in the last five years (see Figure 3). We closely examined the 11 drugs that were approved six or more months more quickly by the EMA compared to the FDA. On the shorter end, Daklinza was approved by the FDA around 11 months following EMA market authorization, whereas on the longer end, Motegrity was granted EMA market authorization nearly 10 years before subsequent FDA approval (refer back to Figure 2).

Figure 3

In the cases of seven of these 11 specific products — Motegrity, Firdapse, Adlyxin/Lyxumia, Wakix, Tresiba, Galafold, and Olumiant — the primary cause for delay was the FDA’s need for additional safety data compared to the EMA. Most of the FDA’s concerns focused on cardiovascular outcomes, such as QT prolongation. However, in the case of Galafold, the initial decision to wait for more safety data was based on GI symptoms. Daklinza was also delayed due to the FDA’s requirement for Phase 3 trial data, rather than the Phase 2 data alone. We surmise that this could have been due to safety concerns.

In the cases of the remaining products — Scenesse, Xadago, and Accrufer/Feraccru — it is not entirely clear based on publicly available information as to why exactly the products were filed first in the EU vs. the U.S. It is plausible that in anticipation of the potential need for longer-term observational real-world evidence (RWE), Clinuvel simply did not file until the safety data were generated for Scenesse.6 Or, as we see occasionally with clients who have a regional geographic presence, the EU may have been prioritized due to greater internal capabilities, know-how, or existing relationships in European markets compared to the U.S.8

Of course, a key element in European markets to consider that we have not yet discussed is HTA decision-making, which is made on a country-by-country basis and further adds time to the total time to commercialization. The duration of these evaluations is variable among, and even within, individual markets and is highly context dependent.

HTA Decision-Making

Individual country-level HTA decisions can add months to years to the total review process. Our analysis of FDA vs. EMA approval did not quantitatively and systematically take into account additional country-level HTA evaluations that occur once EMA market authorization is granted. These HTA decisions have significant implications for product launch and uptake, as positive reimbursement decisions for a product can more quickly lead to broad utilization, whereas products that receive negative assessments frequently flounder commercially. This contributes to why many companies will prioritize the U.S. market opportunity ahead of the EU opportunities.

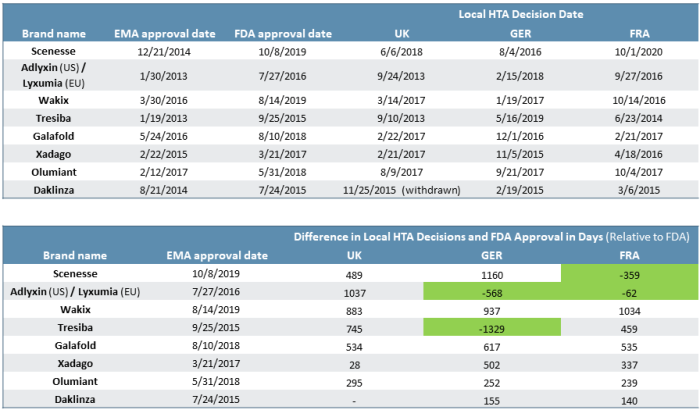

As we see in the examples where three major European markets all completed reviews of the products, market-level reimbursement decisions push out commercialization by anywhere from six months to six years past the EMA market authorization date (see Figure 4). France, the U.K., and Germany were selected, and all tend to have more quantitative evaluations of new pharmaceutical products. Many other markets (EU or otherwise) often reference these markets’ evaluations.

Figure 4

In effect, the difference in FDA vs. EMA approval can further be shifted back such that the effective time to market for the U.S. even more frequently is ahead of European markets and by a wide margin. In our data set, there were four instances in which products that were first approved by the EMA underwent HTA review that subsequently resulted in the FDA approving the product ahead of local EU market reimbursement decisions (see green cells in Figure 4).

Conclusion

There are, of course, additional cases beyond those covered above in which the U.S. has not been the first country to approve novel therapeutics, including a few notable cases:

- bluebird’s Zynteglo (lentiglobin), approved first in the EU for β-thalassemia, a disease that has a higher prevalence in Europe compared to the U.S. and other parts of the world

- BMS’/Ono’s Opdivo (nivolumab), approved first in Japan, likely due to several incentives from the government provided when novel drugs are first approved in Japan17

Even still, nearly four out of every five products that are approved by both the FDA and EMA are first approved in the U.S., typically by a margin of six to nine months sooner. Examining the other one in five products in which the EMA grants market authorization first, roughly half are granted market authorization zero to six months ahead of the FDA. For the remaining 11 outliers approved by the EMA six months to two years or longer ahead of the FDA, the majority were stalled by the FDA out of a requirement for longer-term safety data (often cardiovascular). In several cases, the long-term safety data was generated by the European launch and the EU patient experience before being greenlit by the FDA.

Importantly, this analysis excluded 123 products that are FDA approved but that are not yet approved by the EMA; a subset of these (likely meaningful) are novel products that are likely to eventually receive EMA approval. Given the nature of the question we are exploring, these products would be included in the tally of the total count of FDA approved products that were first launched in the U.S. compared to the EU, further skewing the numbers in favor of the U.S. receiving approvals earlier.

There are numerous factors that companies consider when determining launch sequencing. Most frequently, we find that understanding the U.S. commercial opportunity is the highest priority and easiest to assess due to:

- Robust healthcare infrastructure to identify and thus to treat patients

- Consolidation of academic research and KOLs at U.S. medical centers for many diseases

- High achievable launch prices compared to other major markets such as the EU and Japan and the ability to push through regular price increases

- Fragmentation of payer stakeholders compared to single payer systems in the EU and elsewhere

- Lack of additional reimbursement decision-making such as seen in the EU with individual country-level HTA decisions that can extend the time to commercialization

While the FDA publishes the submission date for NDA and BLA applications, unfortunately the EMA does not. Therefore, there are two scenarios to consider:

- Manufacturers file drug applications with the FDA and EMA at roughly the same time; thus, the earlier FDA approval indicates a quicker overall regulatory process.

- The regulatory processes for FDA and EMA approval take roughly the same amount of time; thus, the earlier FDA approval indicates a prioritization of submitting first to the FDA to access the U.S. market sooner.

In either scenario, the outcome is clear: the U.S. is frequently first in line to access the most innovative pharmaceutical products.

Sources:

- https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/143895-prucalopride-tablets-motegrity

- http://www.pmlive.com/pharma_news/shire_bags_us_approval_for_constipation_drug_motegrity_1272981

- https://investors.biomarin.com/2010-04-19-BioMarin-Launches-Firdapse-in-the-European-Union

- https://www.biospace.com/article/after-2016-rejection-catalyst-wins-approval-for-lems-treatment-firdapse/

- https://www.clinuvel.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/20200323-US-Distribution-Update.pdf

- https://www.clinuvel.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/20180905_US_FDA_Update.pdf

- https://www.pharmalive.com/reaching-epic-proportions-2013/

- https://www.shieldtherapeutics.com/about/our-strategy-values/

- https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211150Orig1s000RiskR.pdf

- https://www.iddt.org/news/degludec

- https://www.biospace.com/article/amicus-plummets-on-3-year-delay-to-u-s-fabry-drug-fda-filing-plan-/

- https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amicus-fda/amicus-therapeutics-receives-u-s-approval-for-fabry-disease-drug-idUSKBN1KV2D5

- https://www.newron.com/about-us/board-of-directors

- https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/after-eu-yes-fda-says-no-to-lillys-baricitinib/440491/

- https://www.fiercepharma.com/regulatory/bristol-myers-gets-approval-gilead-didn-t-want-daklinza-sovaldi-for-hep-c

- https://www.hepmag.com/article/Daklinza-Sovaldi-daclatasvir-27556-2027492363

- https://www.bio.org/sites/default/files/legacy/bioorg/docs/

BioCentury_Cover_AccessInnovationJapan.pdf

About The Authors:

Brendan J. Wang is an engagement manager at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, where he leads teams in supporting biopharma and medtech projects across a wide range of therapeutic areas, from rare and orphan disease indications to novel immuno-oncology therapies. Wang frequently guides clients on commercial opportunity assessments for novel therapeutics and prioritization of indications and assets for further development. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.

Brendan J. Wang is an engagement manager at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, where he leads teams in supporting biopharma and medtech projects across a wide range of therapeutic areas, from rare and orphan disease indications to novel immuno-oncology therapies. Wang frequently guides clients on commercial opportunity assessments for novel therapeutics and prioritization of indications and assets for further development. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.

Christian Thienel is an engagement manager at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, working at every stage and sector of commercial development, with expertise across many therapeutic areas, including NASH and related metabolic diseases, rare diseases, immunology, and oncology. Thienel leads and supports a variety of engagements, primarily focused on portfolio planning and prioritization, pricing and market access strategy, translational development strategy, and licensing strategy. His work spans clients of all sizes, from virtual/concept-stage startups to global life sciences companies. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.

Christian Thienel is an engagement manager at Back Bay Life Science Advisors, working at every stage and sector of commercial development, with expertise across many therapeutic areas, including NASH and related metabolic diseases, rare diseases, immunology, and oncology. Thienel leads and supports a variety of engagements, primarily focused on portfolio planning and prioritization, pricing and market access strategy, translational development strategy, and licensing strategy. His work spans clients of all sizes, from virtual/concept-stage startups to global life sciences companies. Connect with him at info@bblsa.com.