Frequent Deficiencies In GMP Inspections, Part 2

by Lea Joos, The Government of Upper Bavaria

Part 1 of my article series dealt with inadequate handling of deviations and changes. In this article, I share insights on frequent deficiencies regarding cleaning validation.

Assumptions Lead To Insufficient Cleaning Validation

The deficiency: During the cleaning validation, the permitted daily exposure (PDE) values of the active ingredients were determined in order to implement the EMA guideline on setting health-based exposure limits for use in risk identification in the manufacture of different medicinal products in shared facilities. For a combination drug, only the higher dosed active substance was considered, because the risk assessment assumed that the lower dosed active substance is no longer detectable when the higher dosed active substance is cleaned to an acceptable level. Neither the PDE nor the cleanability or solubility of the lower-dose active substance was included in this informal risk assessment. The previous worst-case substance was retained without further rationale.

Furthermore, the following points were not comprehensible from the PDE reports:

- Extent or completeness of the literature search with indication of the data used

- Selection criteria of the lowest observed effect level (LOEL) used for the calculation

(Ref.: EU GMP Guide Part I No. 5.21 and Annex 15 No. 10.6)

What Was The Problem?

The shortcoming was twofold:

First: Insufficient integration of PDE values in the worst-case concept of cleaning validation

In the present case, PDE had not been calculated for all active substances, because the company assumed that nothing is left after the cleaning of active substance A up to its limit value of active substance B, so a PDE calculation for active substance B was not considered necessary.

The assumption that an active substance is no longer present is fundamentally difficult: how many decimal places in which unit mean that substance B is no longer present?

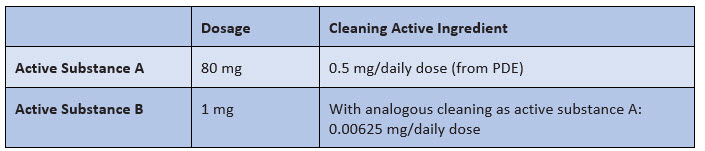

A sample calculation illustrates this problem (see Figure 1):

Figure 1:Assumption of a comparable cleaning of active substance A and active substance B

Does 0.00625 mg (or 6.25 µg) mean that "nothing" is left?

I hope you would answer this way: it depends. In fact, it depends on the potency/toxicity of active ingredient B, i.e., the PDE value. And that brings us to the real problem: the assessment of whether a no-matter-how-low value is low enough after purification can only be made by means of a PDE — and that was missing in this case.

Furthermore, the company did not question whether the cleaning of active substance B is actually equally good and whether this conclusion by analogy is possible at all. For example, active substance A could be very soluble in water, whereas active substance B could be poorly soluble — so the two substances would show different behavior during cleaning.

Irrespective of the various other PDE values for active substances C and D, active substance A, previously defined as the worst-case active substance, was still defined as the worst-case active substance. There was no evaluation of the continued validity of the classification as worst-case active substance based on the calculated PDE values for active substances A, C, and D.

Second: Deficiencies in the PDE report

From the PDE report itself, it was not possible to identify which databases had actually been used for the literature search. It therefore was not possible to assess whether the literature search was carried out completely in accordance with the EMA Guideline on setting health based exposure limits for use in risk identification in the manufacture of different medicinal products in shared facilities.

The PDE report derived the PDE value for active substance A from the LOEL. However, the EMA guideline requires the derivation of the no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) first. If the NOAEL is not used or if several NOAELs exist, it must be justified why for further calculation. This justification is missing.

The Most Common Pitfall

To the first part of the deficiency

The existing concepts of cleaning validation usually provide for worst-case approaches, with validation of only a few active substances representative of all active substances. At the time of the introduction of the EMA guideline, the worst-case active substance was already established in the companies — even if based on a different approach.

The result was that the calculation of PDE values for the active substances was often carried out without a concrete concept for integrating the PDE values into the existing concept for cleaning validation. The worst-case active substance was not questioned.

In the present case, neither the worst-case active substance was questioned nor was it questioned whether, against the background of the PDE values, it can actually be said that nothing more of the second active substance is present in the combination preparation after the first active substance has been purified in accordance with PDE.

To the second part of the deficiency

Very few companies have their own toxicologists who can prepare a PDE report or check the quality of a PDE report. Non-toxicologically trained employees usually do not feel up to testing a PDE report. For them, it is a book with seven seals.

So companies bring in external toxicologists to prepare and file PDE reports. In doing so, they often accept the experts' evaluations uncritically and unchecked, overlooking their own responsibility. How To Avoid This Error

To the first part of the deficiency

For the integration of PDE values in the cleaning validation, a concrete concept should exist that should be able to answer the following questions:

- For which substances must PDE reports be prepared? And for which not? What criteria are applied for this?

- Can different active substances be grouped together for the PDE report? What would be required for this?

- How is the PDE value included in the derivation of the worst-case (active) substance? Which criteria are included in addition to PDE? What is the weighting? Are there criteria that always must lead to consideration in the validation?

- Can PDEs/ADEs be transferred to medicinal products from a toxicological point of view in a non-drug context? Which (minimum) criteria must be met?

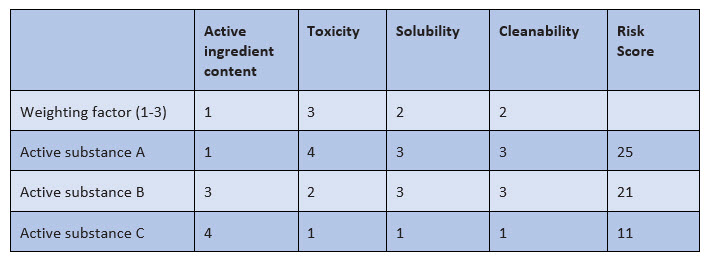

The selection criteria for determining the worst-case product include, for example, active substance content, solubility, and therapeutic dose. Other criteria that also havebeen used so far include cleanability and toxicity. Toxicity can now be very well substantiated with the result of the PDE report and should be taken into account accordingly in the selection of the worst-case product. The weighting of the various selection criteria must be risk-based, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Example of weighting of selection criteria for the worst-case substance

In this example, an evaluation from 1 to 4 is made with the following meaning:

- Active ingredient content: very low (1) to very high (4)

- Toxicity: very low (1) to very high (4)

- Solubility: very good (1) to very poor (4)

- Cleanability: very good (1) to very poor (4)

For the selection criteria, weighting is done by factors of 1 to 3, and weighting the toxicity by a factor of 3 means that the respective toxicity value is multiplied by 3 in order to make the toxicity more relevant in the final evaluation.

Example:

- Without the weighting, the sum of the assessment factors for active substances A and B is 11 each.

- Taking into account the weighting factors, the final assessment factor for active substance A amounts to 25 and for active substance B, it is 21; the toxicity is thus more strongly reflected in the final evaluation.

For such an evaluation, it is necessary to group the PDE values, e.g., PDE 1-50 µg/day, into "toxicity high" (group 3). Such groupings may not adequately reflect the criticality of an active substance in individual cases. In such cases, the active substance must be considered as a worst-case active substance on the basis of a single criterion, e.g., PDE value or solubility alone.

It is very difficult to justify not having a PDE value calculated for individual active substances. This is because toxicity must be taken into account in addition to other criteria such as active substance content and cleanability. And how do you substantiate this if not with the PDE value?

So far, we've been speaking about the EMA guideline, but the spirit of the guideline is not unique to the EU. For example, the FDA's 21 CFR 211 requires specifications, approaches, and decisions to be scientifically justified.

For activities that you carry out according to SOPs or other instructions, such as manufacturing instructions, this scientific justification is usually given. However, as soon as you are in an area that goes beyond this, remember this question.

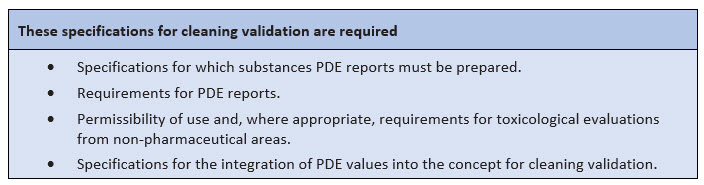

To the second part of the deficiency

The company should formulate its own requirements for external toxicological reports that can be reviewed by non-toxicologists. In principle, this is a matter of logical traceability of the toxicologist's information, especially in the following areas:

- Type and scope of the literature search with indication of the databases.

- Criteria for deriving the most relevant NOAEL or justification for using a lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL).

- Criteria for deriving the correction factors for the PDE calculation.

Then, non-toxicological staff can check the compliance with these criteria and exclude gross errors, e.g., with regard to literature research or comprehensible documentation.

Figure 3: Important specifications for cleaning validation

This article is an excerpt from GMP knowledge contained in the online portal GMP Compliance Adviser, which provides in-depth information about GMP best practices and regulations with a focus on Europe, but also referring to the U.S., Japan, and international organizations PIC/S, ICH, WHO, etc.

About The Author:

Lea Joos has worked as a GMP inspector for the government of Upper Bavaria since 2012. Her tasks include the monitoring of GMP and GDP operations as well as tissue facilities for pharma companies. After studying pharmacy, Joos initially worked as a research assistant at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. In 2012, she began her career with the authorities. Since 2015, she also has acted as a speaker on GMP and GDP topics. She can be reached at lea.joos@gmx.de.

Lea Joos has worked as a GMP inspector for the government of Upper Bavaria since 2012. Her tasks include the monitoring of GMP and GDP operations as well as tissue facilities for pharma companies. After studying pharmacy, Joos initially worked as a research assistant at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. In 2012, she began her career with the authorities. Since 2015, she also has acted as a speaker on GMP and GDP topics. She can be reached at lea.joos@gmx.de.