Introduction To The New ASTM E3418, Standard Practice For Calculating Scientifically Justifiable Limits Of Residues For Cleaning Of Pharmaceutical And Medical Device Manufacturing Equipment And For Medical Devices

By Andrew Walsh, Thomas Altmann, Ralph Basile, Alfredo Canhoto, Ph.D., Stéphane Cousin, Delane Dale, Parth Desai, Boopathy Dhanapal, Ph.D., Jayen Diyora, Christophe Gamblin, Igor Gorsky, Jove Graham, Benjamin Grosjean, Reto Luginbuehl, Spiro Megremis, Ovais Mohammad, Mariann Neverovitch, Rod Parker, Jeffrey Rufner, Siegfried Schmitt, Ph.D., Osamu Shirokizawa, Stephen Spiegelberg, Ph.D., and Randall Thoma, Ph.D.

Part of the Cleaning Validation For The 21st Century series

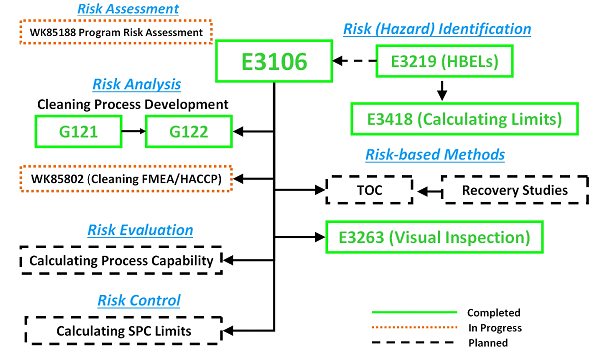

The ASTM E55 Cleaning Team has developed and successfully balloted a new standard practice for calculating safe and scientifically justifiable limits for residues found after cleaning processes. This is the first comprehensive guide to setting limits for use in cleaning validation that includes all types of chemical residues, bioburden residues, endotoxin residues, and visual residues with example calculations for swab and rinse sample limits for pharmaceutical and medical devices applications. This new standard now joins the four previously published standard guides that have been developed by the ASTM E55 Cleaning Team to support the ASTM E3106 Standard Guide1 along with several others that are currently in development or planned (see Figure 1). This ASTM Work Item was balloted, and approved by, the ASTM E55 Pharmaceutical Standards Committee and is now available on the ASTM website. It should be noted that this is the first such standard published in more than 10 years and provides a comprehensive view of all the possible situations arising in the field of measuring cleaning process efficiency. The authors assert that the ASTM E3418 supersedes all currently available industry guidance on this subject.

g

g

Figure 1: ASTM Cleaning Standards for Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices – Completed, In Progress, and Planned. The planned standards shown may undergo changes in scope as they are developed and there may be more standards developed than are listed here.

E3106 – Standard Guide for Science-Based and Risk-Based

Cleaning Process Development and Validation1

G121 – Standard Practice for Preparation of Contaminated Test Coupons

for the Evaluation of Cleaning Agents2

G122 – Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Effectiveness

of Cleaning Agents and Processes 3

Pharmaceutical Discussion

The origins of the calculation of cleaning validation limits for pharmaceuticals date back to the 1980s with the publication of an article in 1984 that stated that "limits must be safe and acceptable and in line with residual limits set for various substances in foods.”4 A second article in 1989 expanded upon these ideas, adding that an "effect threshold" should be established in collaboration with toxicology and medical authorities (or, alternatively, an appropriate safety factor, e.g., 10X or 100X, could be superimposed) and finally that limits for surface residue levels could then be calculated based on a smallest batch size/maximum dose combination. This article further mentioned that this calculation leads to many limits that could be verified through visual inspection.5 A third article in 1993 proposed the use of a combination of limits, suggesting that carryover of product residues needed to meet these three criteria:

- No more than 0.001 dose of any product will appear in the maximum daily dose of another product.

- No more than 10 ppm of a product will appear in another product.

- No quantity of residue will be visible on the equipment after cleaning procedures are performed.6

Many companies, but not all, adopted this approach wholly or in part. Some companies even opted to alter this approach and use 0.01 dose or 100 ppm based on early recommendations in the PDA Technical Report 29 initially published in 1998.

Also in July of 1993, the FDA issued a guide for its inspectors that mentioned these three criteria; it is important to understand that FDA does not endorse or impose these limits but simply stated that they “have been mentioned by industry representatives in the literature or in presentations.” The guide ultimately required that "the basis for any limits must be scientifically justifiable."7

Then, in 1996, FDA proposed that, in addition to penicillin, certain "classes" of compounds would also need to be manufactured in dedicated facilities and that FDA would expect manufacturers to identify any drugs that present the risk of cross-contamination and to implement measures necessary to eliminate that risk.8 Otherwise, nothing short of dedicated facilities or equipment would be sufficient. In 2005, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) similarly announced that it would require dedicated facilities for certain medicines in addition to potent sensitizers.9 Interestingly, the FDA Center of Veterinary Medicine allows manufacturing of penicillin and cephalosporin in non-dedicated facilities.10

In response to these pending regulatory requirements, a guideline was published in 2010 by the International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) that introduced the concept of a health-based limit for calculating cleaning limits known as the acceptable daily exposure (ADE).11 The demonstration of adequate cleaning and control against ADE derived limits could avoid facility or equipment dedication. Several articles were published discussing why the dose-based and median lethal dose (LD50) should no longer be used and should be replaced with the limits based on the ADE.12-15

In 2014, EMA issued a guidance requiring the use of health based exposure limits (HBELs) in calculating cleaning limits.16 This requirement has now been incorporated into the European and Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-Operation Scheme Good Manufacturing Practices17, 18 and has been adopted by Health Canada19 China20 and the World Health Organization.21

Medical Device Discussion

The medical device industry is very broad and manufactures many diverse devices that have been handled differently than pharmaceuticals.

For example, cleaning acceptance limits for implantable medical devices have been based historically on testing after the cleaning process is completed by doing biological safety assessments that show that the final packaged product is safe and effective.22-25 Initial cleaning limits might be derived from historical data on the same types of devices using the same manufacturing processes and materials as a starting point and coupling that with clinical history that shows the devices produced using this methodology are safe and effective. Then biological safety testing, which would include any extractables, is performed on devices exposed to the validated, controlled cleaning process.

The biological safety testing (which includes extractables) also shows that the limits that were established for other manufacturing residuals that carry over on the part after cleaning are at levels low enough to eliminate any local or systemic adverse reaction. (This may be a toxicological risk assessment of the extractables test data as well as biological testing.)

While many medical devices use the approach described above, some medical devices can benefit from using an HBEL approach similar to that used for pharmaceuticals. If an HBEL approach is used with a medical device, a risk assessment (this could be the HBEL Monograph developed from ASTM E321926) should address other potential risks (e.g., patient exposure at the tissue level) from residue levels on the device beyond the general toxicological risk assessments typically performed for pharmaceuticals.

Scope Of ASTM E3418

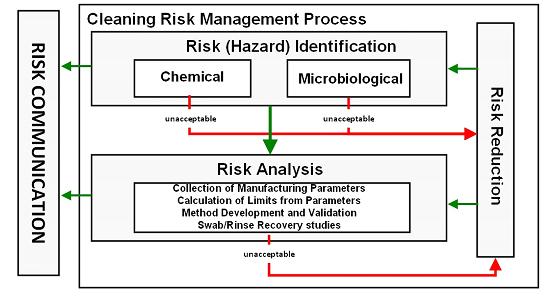

The E3418 standard practice provides procedures for calculating safe and scientifically justifiable limits of residues for use in cleaning validation studies of pharmaceutical/biopharmaceutical/medical device manufacturing equipment surfaces and for medical device surfaces in accordance with ASTM E3106 Standard Guide (Figure 2). The procedures in this standard practice for calculating safe limits of chemical residues are based on the practices outlined in ASTM E3219.26

Figure 2: Risk (Hazard) Identification and Risk Analysis Steps of ASTM E3106 (modified from Figure 3 in E3106) - All medicinal products must have HBELs determined15. Other chemical compounds identified as hazards to patients in the Risk (Hazard) Identification Step that cannot be eliminated or replaced should have HBELs determined if acceptable safety assessments or risk assessments are not available (ASTM E3219).26 After HBELs have been determined, manufacturing parameters such as batch sizes, maximum daily doses, total share surface areas, etc. are documented in the Risk Analysis Step and used to calculate safe limits for swab and rinse samples.

ASTM E3418 applies to:

Pharmaceutical Residues

This includes active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs); dosage forms; and over-the-counter, veterinary, biologics, and clinical supplies. This guide is also applicable to other health, cosmetics, and consumer products.

Chemical Residues

This standard practice applies to all types of chemical residues, including intermediates, cleaning agents, processing aids, machining oils/lubricants, etc. that could remain on manufacturing equipment product contact surfaces or on medical devices that have undergone all manufacturing steps, including cleaning. This standard practice does not cover extractables and leachables (see ISO 10993-18, 2023.)24

Microbiological Residues

This standard practice applies to microbiological and endotoxin residues that may be present on manufacturing equipment product contact surfaces or on medical devices that have undergone all manufacturing steps, including cleaning, but does not cover disinfection, sterilization, or depyrogenation. It is important to separate the cleaning process from disinfection, sanitization, and sterilization processes, as cleaning comes before these later operations.

Visual Residues

This standard practice applies to visual residues that may be present after cleaning pharmaceutical or medical device manufacturing equipment surfaces or medical devices’ surfaces. ASTM E3418 references and supports the principles described in ASTM E3263 Standard Practice Guide.27

Residues on Medical Devices

This standard applies to medical devices that make patient contact following all manufacturing and cleaning. Medical devices that do not make patient contact are excluded.

Significance And Use Of ASTM E3418

The ASTM E3418 guide applies the science-based and risk-based concepts and principles for calculation of cleaning validation safe limits and performance-based limits (e.g., statistical process control) introduced in ASTM E3106. The ASTM E3418 guide applies the science-based and risk-based concepts and principles for derivation of HBELs introduced in ASTM E3219.26 This guide also applies the science-based and risk-based concepts and principles for derivation of visual residue limits introduced in ASTM E3263.27 All limit calculations in this standard assume there will be homogeneity of residue levels on equipment and device surfaces achieved after an effective and consistent cleaning as per ASTM E3106.

Calculations In ASTM E3418

Users of the standard will need to define what equipment should be included in the calculation of limits (e.g., single pieces of equipment vs. equipment trains). This decision should be based on a risk assessment of the scope of the cleaning process. This standard does not recommend calculating a single limit for all cleaning processes, for all equipment and manufacturing trains, within a facility.

For pharmaceuticals and medical device products that use the HBEL, the equations used for calculating safe and scientifically justified swab and rinse sample limits are composed of three sub-equations:

- Health Based Exposure Limit (HBEL)

- Maximum Safe Carryover (MSC)

- Maximum Safe Surface Residue (MSSR)

Subsequent sections discuss the various parameters used in the calculation of these sub-equations, how these parameters should be determined or derived, and how they interact with each other. The first three sub-equations are generally combined into one general equation that calculates a safe analytical limit, usually a swab or rinse limit.

The E3418 is a comprehensive guide containing details for each of the following sections.

Calculating Health Based Exposure Limits – This section contains guidance and references on the derivation of HBELs using ASTM E321926 and also includes a discussion on:

- use of substitute limits

Calculation of the Maximum Safe Carryover (MSC) of Residue into Next Product Batch – This section discusses how the MSC is calculated using the following parameters with several options for different situations:

- smallest batch size (SBS)

- maximum daily dose (MDD)

- batch size/daily dose ratio using quantities

- batch size/daily dose ratio using dosage units

- batch size/daily dose ratio using API quantities

- device/residue per device for medical devices

Calculation of the Maximum Safe Surface Residue (MSSR) – This section discusses how the MSSR is calculated from the following parameter.

- total shared surface area (TSSA)

Calculation of the Safe Limit in Analytical Samples – This section discusses how safe swab limits can be calculated from the MSSR and the following parameters.

- swab area (SA)

- swab dilution volume (SDV)

Calculation of the Rinse Sample Safe Limit – This section discusses how safe rinse limits can be calculated from the MSSR and the following parameters.

- rinse area (RA)

- rinse volume (RV)

- rinse volume determination (what volume to use):

- based on volume-to-surface area ratio

- based on the solubility of the residue

- based on the quantitation limit of the analytical method

- based on spray ball coverage testing

- minimum working/batch volume

- volume used for final rinse sampling

- volume sufficient to submerge the surface

Percent Organic Carbon Content (%C) – This section discusses how the percentage of organic carbon in a compound is calculated and how to apply it to adjust either acceptance limits or to adjust swab/rinse data.

Calculating Swab/Rinse Safe Limits for Cleaning Process Residues (APIs/Pharmaceuticals/Biopharmaceuticals) – This section provides the full calculations of swab and rinse samples for use in pharmaceutical situations with several examples of each calculation.

Calculating Swab/Rinse Safe Limits for Cleaning Process Residues (Medical Devices) – This section provides the full calculations of swab and rinse samples for use in medical device situations with several examples of each calculation.

Recovery Factors (Swab/Rinse) – This section discusses how the factors from swab or rinse recovery studies are derived and how to apply them to adjust either acceptance limits or to adjust swab/rinse data.

Setting Safe Limits for Cleaning Agents – This section discusses approaches for setting safe limits for cleaning agents and provides an example calculation.

Setting Safe Limits for Organic Solvents - This section discusses approaches for setting safe limits for organic solvents using ICH Q3C (R5) and provides an example calculation.

Setting Safe Limits for Bioburden – This section discusses approaches to setting safe limits for bioburden for the following situations:

- bioburden limits for non-sterile products

- bioburden limits for sterile pharmaceutical products

- bioburden limits for low bioburden production

- bioburden limits for medical devices

- bioburden limits based on statistical process control

Setting Safe Limits for Endotoxin – This section discusses approaches to setting safe limits for endotoxin.

Setting Safe Limits for Visual Inspection – This section discusses approaches for setting safe limits for visual inspection following ASTM E326325 and provides an example calculation using the visual detection index (VDI) method.

Setting Cleaning Performance Limits – This section provides guidance and references on how to set statistically derived alert and action limits based on actual swab or rinse data. Calculations are provided and two examples for chemical residues and bioburden residues are shown.

There are also discussions on:

- use of historical limits as alert limits

- limits for therapeutic macromolecules and peptides

Summary

The authors believe that the new ASTM E3418 standard provides the first comprehensive guide to setting limits for use in cleaning validation for all types of chemical residues, bioburden residues, endotoxin residues, and visual residues for both pharmaceutical and medical devices applications and should become the main reference for any cleaning subject matter expert (SME) involved in the calculation of cleaning limits.

Peer Review

The authors wish to thank Sarra Boujelben, Gabriela Cruz, Ph.D., Mallory DeGennaro, Andreas Flueckiger, MD, Ioanna-Maria Gerostathi, Ioana Gheorghiev, MD, and Ajay Kumar Raghuwanshi for reviewing this article and for providing insightful comments and helpful suggestions.

References

- American Society for Testing and Materials E3106-18e1 Standard Guide for Science Based and Risk Based Cleaning Process Development and Validation www.astm.org.

- American Society for Testing and Materials G121-18 Standard Practice for Preparation of Contaminated Test Coupons for the Evaluation of Cleaning Agents www.astm.org.

- American Society for Testing and Materials G122-20 Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Cleaning Agents and Processes www.astm.org.

- S. Harder “The Validation of Cleaning Procedures” Pharmaceutical Technology, May 1984.

- D. Mendenhall, “Cleaning Validation” in Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 15(13), 2105-2114 1989.

- G. Fourman and M. Mullin “Determining Cleaning Validation Acceptance Limits for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Operations” in “Pharmaceutical Technology” April 1993.

- "FDA Guide to Inspections: Validation of Cleaning Processes" July 1993, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), www.fda.gov.

- Current Good Manufacturing Practice: Proposed Amendment of Certain Requirements for Finished Pharmaceuticals. Federal Register/Vol. 61 No. 87/Friday, May 3, 1996/Proposed Rules

- EMA Concept paper dealing with the need for updated GMP guidance concerning dedicated manufacturing facilities in the manufacture of certain medicinal products. Doc. Ref. EMEA/152688/04. Feb 2, 2005

- FDA Guidance Questions and Answers on Manufacturing Considerations for Penicillin or Cephalosporin Animal Drugs 1/31/2023

- International Society for Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE), ISPE Baseline Guide: Risk-Based Manufacture of Pharmaceutical Products (Risk-MaPP), first edition, September 2010.

- Walsh, A., “Cleaning Validation for the 21st Century: Acceptance Limits for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs): Part I,” Pharmaceutical Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 4, July/August 2011, pp. 74–83, available from: https://ispe.org/pharmaceutical-engineering-magazine.

- Walsh, A., “Cleaning Validation for the 21st Century: Acceptance Limits for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs): Part II,” Pharmaceutical Engineering, Vol. 31, No. 5, September/October 2011, pp. 44–49

- Walsh, A., Ovais, M., Altmann, T., and Sargent, E. V., “Cleaning Validation for the 21st Century: Acceptance Limits for Cleaning Agents,” Pharmaceutical Engineering, Vol. 33, No. 6, November/December 2013, pp. 12–24

- Walsh, Andrew, Michel Crevoisier, Ester Lovsin Barle, Andreas Flueckiger, David G. Dolan, Mohammad Ovais (2016) "Cleaning Limits—Why the 10-ppm and 0.001-Dose Criteria Should be Abandoned, Part II," Pharmaceutical Technology 40 (8)

- European Medicines Agency, “Questions and answers on implementation of risk-based prevention of cross-contamination in production” and “Guideline on setting health-based exposure limits for use in risk identification in the manufacture of different medicinal products in shared facilities,” 19 April 2018, EMA/CHMP/CVMP/SWP/246844/2018.

- EudraLex, Volume 4 – Guidelines for Good Manufacturing Practices for Medicinal Products for Human and Veterinary Use, Annex 15: Qualification and Validation, available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/eudralex/vol-4_en.

- Pharmaceutical Inspection Convention - Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-Operation Scheme "Guide To Good Manufacturing Practice For Medicinal Products Annexes" July 2018.

- Health Canada - Cleaning validation guide (GUI-0028).

- National Medical Products Administration Food and Drug Audit and Inspection Center Guidelines for Quality Risk Management in Co-Line Manufacturing of Pharmaceuticals March 2023

- World Health Organization Technical Report Series 1033 -WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations (Annex 2).

- ASTM F3127-22 Standard Guide for Validating Cleaning Processes Used During the Manufacture of Medical Devices www.astm.org.

- ISO 19227:2018 Implants for surgery - Cleanliness of orthopedic implants - General requirements

- ISO 10993-18:2020 Biological evaluation of medical devices - Part 18: Chemical characterization of medical device materials within a risk management process

- ISO 10993-1 Part 1: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process

- American Society for Testing and Materials E3219-20 Standard Guide for Derivation of Health Based Exposure Limits (HBELs) www.astm.org.

- American Society for Testing and Materials E3263-20 Standard Practice for Qualification of Visual Inspection of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Equipment and Medical Devices for Residues, www.astm.org.