Is Open Collaboration The New Paradigm In Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Innovation?

By John Mulgrew, Centre for Continuous Manufacturing and Advanced Crystallization (CMAC), University of Strathclyde

You’ve heard it before. Change comes slowly to a risk-averse industry like pharmaceuticals. How can we reduce these risks and increase the success in adopting new technologies and better supply chains? Part of the answer is better collaboration between industry, academia, and government. These collaborations “represent the future of pharmaceutical manufacturing and the supply chain R&D,” according to the International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineering (ISPE) Facility of the Year Award judges in their honorable mention award to the Centre for Continuous Manufacturing and Advanced Crystallisation (CMAC) based at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, Scotland.

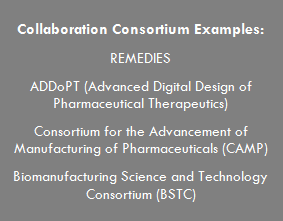

This two-part article focuses on innovation through collaboration (Part 1) and provides a practical example of how this can be achieved (Part 2). Incremental innovation is the norm for successful companies, but this article is about a different path to success: disruptive innovation. An excellent example of disruptive innovation in pharmaceutical manufacturing is demonstrated in a case study highlighting a collaboration that aims to positively impact the small molecule pharmaceutical supply chain, the active pharmaceutical ingredient and starter material work stream within the REMEDIES (RE-configuring MEDIcines End-to-end Supply) project.

REMEDIES, launched in 2014, is part of the Advanced Manufacturing Supply Chain Initiative (AMSCI) program, whose goal is to improve the global competitiveness of advanced manufacturing supply chains. AMSCI, along with Scottish Funding Council, are funding research and development, skills training, and capital investment to help supply chains achieve world-class standards. The £23 million project is headed up by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) with research partners IfM (Institute for Manufacturing) at the University of Cambridge and CMAC at the University of Strathclyde. It brings together key players in the end-to-end supply chain, including major manufacturing organizations, technology and equipment developers, regulators, knowledge transfer networks, and healthcare providers. The project will be completed March 2018 and involves 22-partner organizations. (REMEDIES will be discussed in greater detail in Part 2.)

Customarily, pharmaceutical companies pursued differentiation in the market by internally developing core competencies and shielding these against the outside world as a means to hold onto their competitive advantage. This model, called a closed innovation model, originated in the product development process, a type of science-compelled innovation to deliver new drugs to the market. A lot has changed, however, with companies realizing that their real differentiation is in the molecule, not the process for making it. The traditional model of closed innovation is no longer viable when it comes to medicine manufacturing supply chains because a company has to own a large range of technologies and expertise, the cost of which, in terms of overhead and capital, is not sustainable. In the current market environment, an open innovation strategy, which involves tapping into external knowledge and expertise in non-core areas, is better suited to sustaining a competitive advantage.

Why Innovation Is Desperately Needed

The supply chain structure of the pharmaceutical industry as it relates to in-bound material supply, production footprint in active processing and drug product manufacture, and downstream supply chain operations has not changed for decades. Despite healthy product margins and progressive improvements in production process control and consequent productivity, when compared with other process industries, drug manufacturing operational performance levels are well below process-industry norms on right-first-time quality, inventory, and service levels. Structural changes to pricing models may, in the future, also challenge this strong margin position, as healthcare providers move to a manufacturing cost-based pricing model rather than the “value”-driven pricing arrangements of today.

In terms of quality and the repeatability of manufacturing processes, most pharmaceutical firms operate at levels of between three and four sigma in terms manufacturing right-first-time, costing the global industry some $25 billion annually. Globally, inventory levels for the top 25 pharmaceutical companies exceed $125 billion.1

The current predominantly batch and centralized manufacturing model has resulted in product supply chains that typically are between one and two years in length, with a huge associated cost of inventory. The assets that most Big Pharma companies have for product manufacture are suited to blockbuster supply, relying on large-scale centralized batch manufacturing plants, located predominantly in developed countries. Current trends in the industry suggest that smaller, more niche-volume products will become the norm within a market demand context where globalization will require the ability to supply multiple geographically dispersed locations, collectively representing a more fragmented product portfolio.

The current predominantly batch and centralized manufacturing model has resulted in product supply chains that typically are between one and two years in length, with a huge associated cost of inventory. The assets that most Big Pharma companies have for product manufacture are suited to blockbuster supply, relying on large-scale centralized batch manufacturing plants, located predominantly in developed countries. Current trends in the industry suggest that smaller, more niche-volume products will become the norm within a market demand context where globalization will require the ability to supply multiple geographically dispersed locations, collectively representing a more fragmented product portfolio.

On the other hand, several technology companies, including early-stage companies, SMEs, and academic spin-outs are the innovation drivers looking to bring new products and processes into industrial adoption. This includes equipment manufacturers, analytical and control system providers, and disruptive technology companies involved in additive manufacturing processes, among others. These companies often face large barriers to working with pharmaceutical companies to bring new technologies into manufacturing operations.

The industry has certainly been aware of these changes and the need to execute manufacturing differently. Over the past decade there have been significant investments in continuous manufacturing development, measuring well over a billion dollars in aggregate. These investments have, for the most part, been made by companies pursuing internal projects, with little communication or collaboration across the industry. The consequence is that, while some benefits have been realized, the enormous potential of continuous manufacturing and other new technologies is not yet manifest, and the initial investments have not been recouped.

Innovation, translation, and industrialization of new technologies, where suppliers, end users, and academics work together, will accelerate adoption of improved manufacturing opportunities. Introduction of continuous manufacturing, as an example of a new technology, has the potential to increase quality in terms of manufacturing right-first-time to greater than five sigma, and reduce supply chains to two to six months, thus reducing inventory levels substantially.

Considerations When Trying To Collaborate

In a world of shrinking margins, tight budgets, and risk aversion, how can pharmaceutical manufacturers afford to innovate? And not just innovate in an incremental way, which we are all familiar with, but rather in a disruptive or transformational way that will yield more substantial improvements to quality and cost of manufacturing. Innovation means different things to different people, different organizations, and different products or manufacturing processes. For the purposes of this article, innovation is defined as the implementation of something creative and disruptive to the supply chain that results in added value.  In considering whether to join a collaboration, an honest assessment has to be made about the type of organization you are a part of. Is your organization an innovation leader, early adopter, early majority, late majority, or a laggard? This will inform the type of innovation your organization should pursue or might approve of.

In considering whether to join a collaboration, an honest assessment has to be made about the type of organization you are a part of. Is your organization an innovation leader, early adopter, early majority, late majority, or a laggard? This will inform the type of innovation your organization should pursue or might approve of.

Collaborations have the most impact on the earlier portion of the technology adoption life cycle. In the case of REMEDIES, in particular the active pharmaceutical ingredient work stream, the large pharma and CMOs are early adopters who are working with innovators (technology providers) to move the pharmaceutical industry’s capabilities for continuous manufacturing forward.

The many challenges of getting from applied research to product development are why most new technologies languish; this portion of the innovation process is known as the “valley of death.” In this valley, the risk of failure is still relatively high, usually too risky for many companies. Collaborations are a means of reducing or sharing this risk and increasing the likelihood of success by bringing together a broader and more diverse team to drive adoption of technologies. Collaborations can be viewed as a bridge across the innovation valley of death.

Collaboration projects allow ideas and expertise to flow between industry and academia, resulting in an array of benefits for those involved. For companies, benefits can include more efficient and successful drug development, greater networking, access to talented graduates, reduced risk associated with investing in innovative research, and the potential for increased gross value added (GVA) per cost incurred. For academics, benefits include access to specialized equipment and data, a greater understanding of real-world problems and industrial challenges, increased job prospects, and new funding avenues.

From talking to many people in the pharma industry, it is clear that businesses often face similar challenges when it comes to expanding or taking the next step. A lack of finances or expertise or concerns about risk are familiar barriers, which can cause reluctance and inactivity. Even if your company is eager and active in trying to innovate, going it alone can mean slow progress. Collaboration with other like-minded businesses can provide an opportunity to share the risk and the rewards. By collaborating with others and bringing together diverse expertise, you can create an environment where innovation thrives, opening up a world of opportunities.

How Do I Get There?

Many technology-driven research universities are eager to work with industry to inform their research challenges. Governments are increasingly eager to invest in technology and innovation as a means of driving economic growth.2

The consortium co-operative used for the REMEDIES program is a tried-and-tested way to facilitate collaboration. Made up of organizations that have come together for a common purpose, it runs in a shared and equitable way, working toward achieving a common objective - with companies retaining their own IP, brand identity, independence, and control. Pharmaceutical companies are realizing that their most valuable IP is in the molecule, not in the manufacturing process (although one cannot ignore the potential competitive advantage adopting new technologies in the manufacturing process brings). This is why companies like GSK, AstraZeneca, Robinson Brothers Ltd., and Thomas Swan & Co. Ltd. are partners in REMEDIES, working alongside each other.

One of the biggest challenges to collaborations is getting the appropriate legal framework in place, and adequate time needs to be allocated for each partner’s legal team to weigh in on the consortium agreement; however, standard frameworks, such as the Lambert Toolkit, can help get you started. With REMEDIES, it took the better part of nine months to get all 23 partners signed on. REMEDIES is an especially large consortium; many collaborations involve fewer partners and thus should not take near as much time to implement.

Part 2 of this article will look at the REMEDIES project as a case study in modern pharmaceutical industry collaboration.

References:

- Srai, J. S., Badman, C., Krumme, M., Futran, M. and Johnston, C. (2015), Future Supply Chains Enabled by Continuous Processing — Opportunities and Challenges. May 20–21, 2014, Continuous Manufacturing Symposium. J. Pharm. Sci., 104: 840–849. doi:10.1002/jps.24343

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Policy Brief, September 2000.

About The Author:

John Mulgrew is industry collaboration project manager at CMAC – Strathclyde University’s Centre for Continuous Manufacturing and Advanced Crystallization. He has spent most of his career as a consulting engineer working with pharmaceutical and life sciences organizations to build large-scale manufacturing facilities. John’s studies to complete an MBA in corporate innovation led him to pursue his interest in innovation. He has brought his experience from the pharmaceutical industry together with his project management skills to guide multi-partner, pre-competitive collaborations. He is also working with the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI) to bring the Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Centre (MMIC), an open innovation center dedicated to small molecule pharma manufacturing, to Scotland.

John Mulgrew is industry collaboration project manager at CMAC – Strathclyde University’s Centre for Continuous Manufacturing and Advanced Crystallization. He has spent most of his career as a consulting engineer working with pharmaceutical and life sciences organizations to build large-scale manufacturing facilities. John’s studies to complete an MBA in corporate innovation led him to pursue his interest in innovation. He has brought his experience from the pharmaceutical industry together with his project management skills to guide multi-partner, pre-competitive collaborations. He is also working with the Centre for Process Innovation (CPI) to bring the Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Centre (MMIC), an open innovation center dedicated to small molecule pharma manufacturing, to Scotland.

In addition to his work at CMAC, John enjoys lecturing the project management module for the M.Sc. program in pharmaceutical manufacturing at University of Strathclyde, as well as guest lecturing on project management for various other universities courses.

You can connect with John on LinkedIn and find more information on REMEDIES here.