Regulatory Implications Of The CARES Act On Over The Counter Drugs

By Suzanne O’Shea, Saul B. Helman, David Berger, and Jody Roth, Guidehouse

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in March of 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, reforms how over the counter (OTC) drugs are regulated in the United States. In announcing the legislation, the FDA called the changes a “landmark step that will have an impact lasting long after the current public health emergency.”1

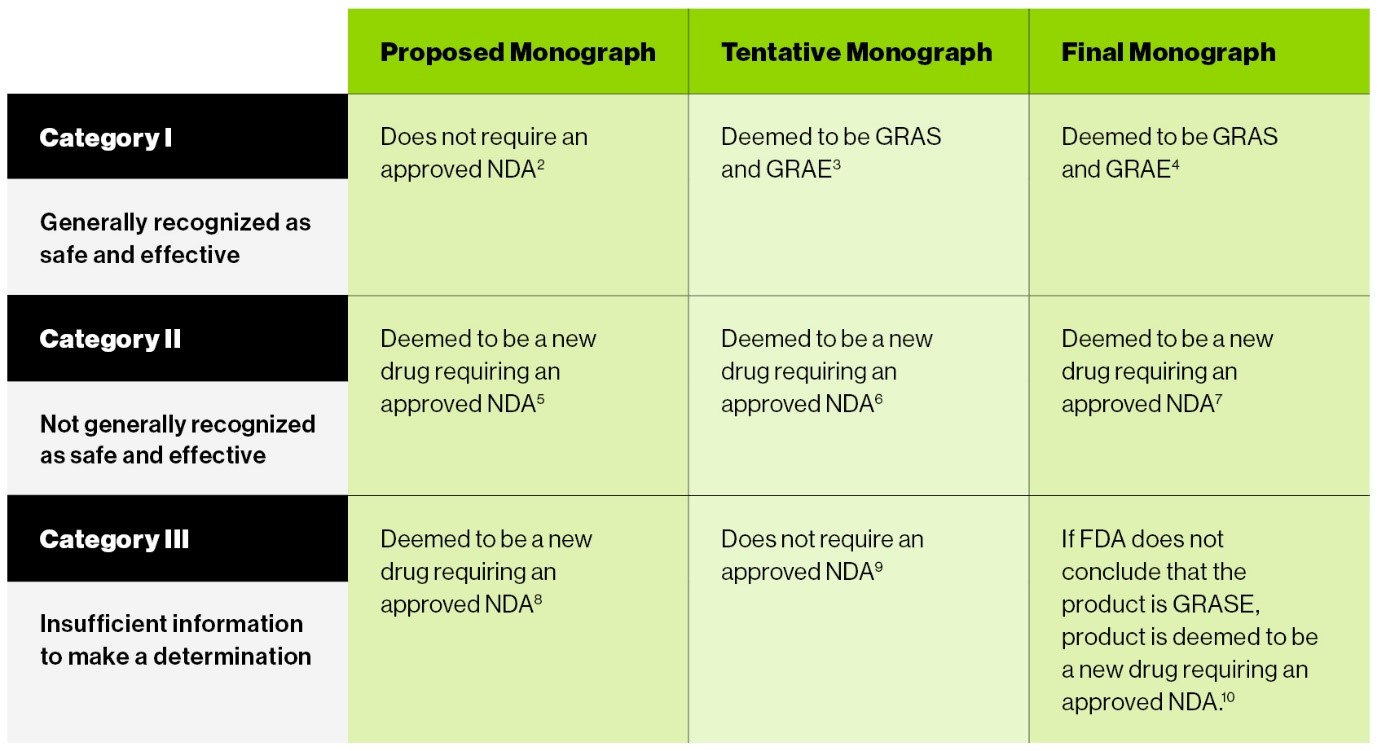

One clear intent of the CARES Act was to “wrap-up” the old OTC monograph process as quickly as possible. To that end, the new law deems products at various stages of review under the old OTC monograph system to be generally recognized as safe and effective, new drugs requiring an approved new drug application (NDA), or products that may be marketed without an approved NDA.

For easy reference, the chart below outlines the status of OTC drugs under the previous OTC monograph system according to CARES:

The CARES Act Creates Options For OTC Drug Manufacturers

Among other things, the CARES Act creates an administrative order process to replace the old OTC drug monograph system. Under the new administrative order system, manufacturers wishing to bring an OTC drug comprised of active ingredient not currently marketed OTC may request the FDA to issue an administrative order permitting the marketing of the product without the need for an approved NDA.

However, the CARES Act states that the law shall not preclude a person from seeking approval of an NDA.2 We understand this statutory provision to mean that manufacturers have the option of seeking an administrative order or NDA approval.

In this article, we discuss factors manufacturers of new OTC drug products may wish to consider in deciding which regulatory route to follow.

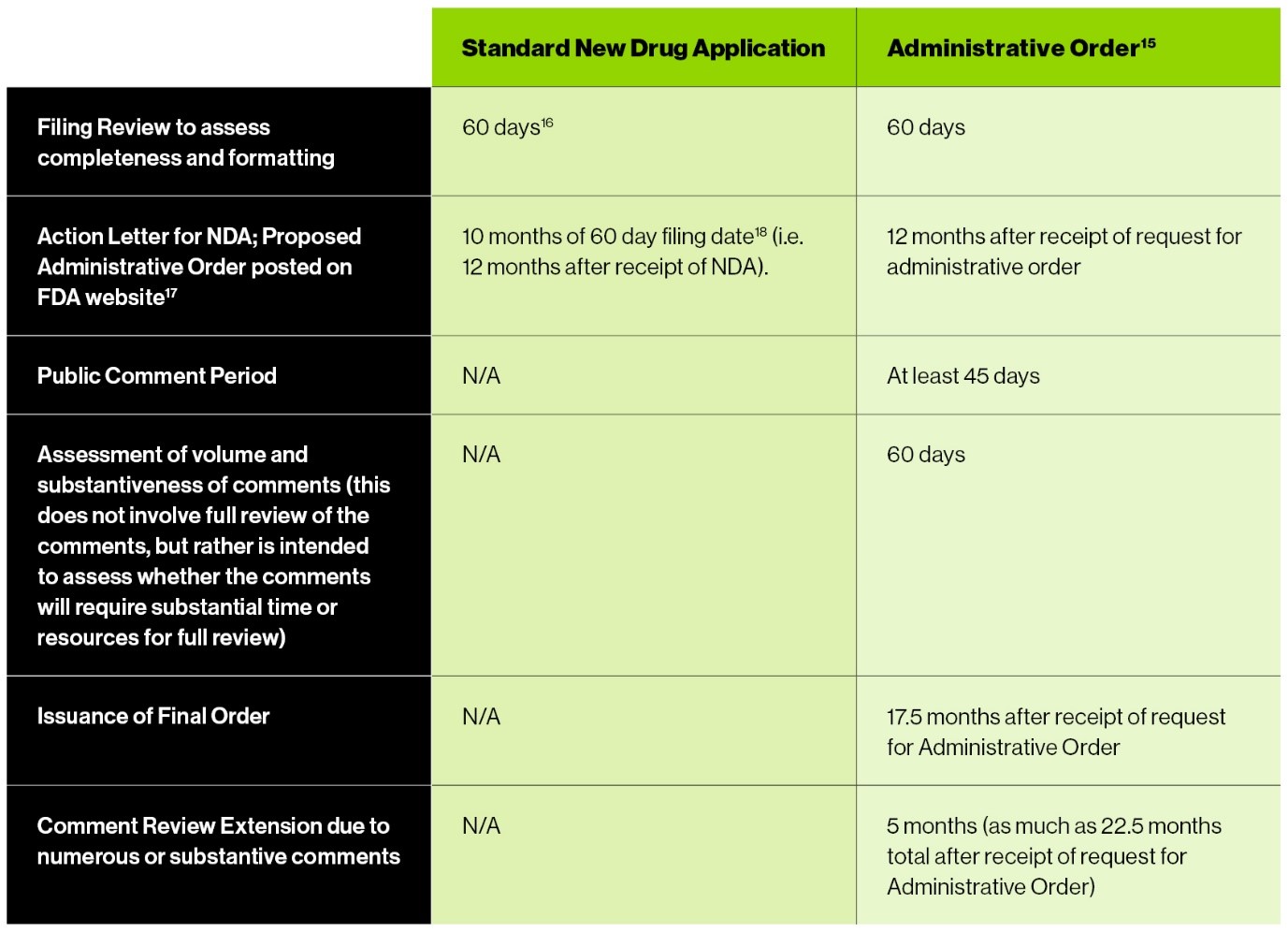

Timing

The CARES Act includes a brief outline of the process the FDA is to follow in determining whether to issue an administrative order; however, it does not provide time frames for completion of these steps.3 The most useful reference in this regard is a letter from FDA leadership to the chairs of certain Senate and House committees that sets goals for FDA completion of various tasks under the CARES Act (Goals Letter).4 The table below compares the time frame for the FDA’s review of a standard NDA with the time frame for issuing a new administrative order:

Confidentiality

The NDA review process is confidential. The FDA cannot even acknowledge the submission of an NDA until it is approved.5 In contrast, under the CARES Act, the FDA is required to make publicly available any information submitted by a person requesting a new administrative order, as well as any information submitted by any other person with respect to the request for a new administrative order.6 The only information the FDA is not required to make available is pharmaceutical quality information and raw datasets.7 This results in a far more open process that invites the participation of interested persons, potentially including the requestor’s competitors, public interest groups, and the general public, and requires the disclosure of essentially all information submitted by all parties.

Exclusivity

The CARES Act provides for an 18-month exclusivity period following the effective date of an administrative order authorizing marketing of an OTC drug with an active ingredient not previously included in an OTC monograph.8 During this time, only the order requestor (or its licensees, assignees, or successors in interest) are authorized to lawfully market the product. Because there is no pre-approval process for products marketed under an administrative order, this exclusivity system relies to some extent on the good faith of competitors to observe the exclusivity period. It remains to be seen how vigorously the FDA will enforce this exclusivity period by taking action to remove products that have entered the market early. At the end of the 18 months, any drug product conforming to the administrative order can be marketed without approval of an NDA or other authorization by the FDA.9

In contrast, upon approval of an NDA for a new chemical entity, no one can submit a 505(b)(2) or 505(j) application for a product that contains the same active moiety for a period of four or five years.10 When an NDA (or NDA supplement) is approved for an active moiety that has previously been approved, and new clinical investigations were required to support approval of the NDA or supplement, then the FDA may not approve, for a period of three years, any 505(b)(2) or 505(j) application that relies on information supporting the change in the NDA or supplemental NDA.11 Thus, the potential exclusivity period associated with an NDA is far stronger and longer than the exclusivity period associated with an administrative order.

Effectiveness

The effectiveness data required to support an NDA and an administrative order are similar. NDA approval requires the submission of substantial evidence of effectiveness; this is typically interpreted as requiring at least two adequate and well-controlled clinical trials.12

A request for an administrative order must include data demonstrating that the product is generally recognized as safe and effective under Section 201(p)(1) of the Act,13 which relies on “experts qualified by scientific training and experience” to evaluate effectiveness.14 In addition, current FDA regulations state that proof of effectiveness of OTC drugs “shall consist of controlled clinical investigations as defined in 314.126(b),”15 which describes the characteristics of an adequate and well-controlled clinical trial. In any particular case, manufacturers should carefully consider whether the data requirements of an NDA or administrative order differ significantly.

Safety

The CARES Act expands how drug sponsors seeking authorization to market an OTC product may demonstrate the safety of the product as compared to an NDA. This requirement can be met by showing that the drug was marketed and safely used under comparable conditions of marketing and use in the European Union, European Free Trade Association, Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland, South Africa, or other designated countries, for a period of time sufficient to provide reasonable assurances of the safe nonprescription use of the drug. In addition, the sponsor must show that during the time of nonprescription use of the drug in one of the identified countries, the drug was subject to sufficient monitoring by a regulatory body, including reporting of adverse events.16

In this way, safety information from an identified country provides prima facie evidence of the safety of the product for OTC use, meaning that this evidence is sufficient unless the FDA identifies a reason why the product would not be considered safe for OTC use in the U.S. In practice, the FDA will likely consider cultural fit in the process to determine safety, so it may be that some OTC products from the listed countries will still have to show safety in the U.S. Nevertheless, in some instances, this new statutory provision could help open the door to marketing of OTC products currently sold only outside the U.S.

User Fees

The fees associated with a new administrative order are significantly less than a new drug application fee. Companies requesting an administrative order for a new OTC drug product will be required to pay a $500,000 user fee,17 funds the FDA says will be reinvested to “support the agency’s monograph drug activities” and help accelerate drug availability.18 In contrast, in FY 2020, an application fee for an NDA supported by clinical data is $2,942,965.19

Conclusion

The new administrative order process created by the CARES Act will almost certainly proceed more quickly than the old OTC drug monograph system. However, given the various advantages and disadvantages of the new OTC administrative order process compared to the existing NDA process, and the continuing availability of the NDA process, we recommend that manufacturers seeking to introduce new products to the U.S. OTC market carefully consider how the two processes align with their business objectives.

References:

- FDA on Signing of the COVID-19 Emergency Relief Bill, Including Landmark Over-the-Counter Drug Reform and User Fee Legislation

- Section 505G(f)

- Section 505G(b)(5)(A); 505G(b)(2)

- Section 3861 the CARES Act. The Goals Letter is available here: https://www.fda.gov/media/106407/download

- 21 CFR 314.430(b). See also 21 CFR 312.130

- Section 505G(d)(2)(A)

- Section 505G(d)(2)(B)

- Section 505G(b)(5(C)

- Section 505G(b)(1)(B)

- 21 CFR 314.108(b)(2)

- 21 CFR 314.108(b)(5)

- Section 505(d)(5)

- Section 505G(b)(5)(i)(I)

- Section 201(p) of the Act

- 21 CFR 330.10(a)(4)(ii)

- Section 505G(b)(6)(C)

- Section 744M(a)(2)(A)(i) of the Act

- Over the Counter Monograph User Fee Program, FDA

- Federal Register of August 2, 2019, 84 FR 37882

About The Authors:

Suzanne O’Shea, JD, is a director in Guidehouse's Life Sciences and FDA Regulatory practice. Her areas of expertise include strategic analysis of regulatory pathways depending on unique client circumstances in evolving areas of regulation such as combination products, laboratory developed tests, and Section 361 status of human tissue products. She also advises clients in the areas of informed consent, investigator disqualification proceedings, Form 483/Warning Letter responses, quality agreements, good manufacturing practices for combination products, and review of promotional materials for products of all types. Additionally, she serves as an expert witness on FDA processes.

Suzanne O’Shea, JD, is a director in Guidehouse's Life Sciences and FDA Regulatory practice. Her areas of expertise include strategic analysis of regulatory pathways depending on unique client circumstances in evolving areas of regulation such as combination products, laboratory developed tests, and Section 361 status of human tissue products. She also advises clients in the areas of informed consent, investigator disqualification proceedings, Form 483/Warning Letter responses, quality agreements, good manufacturing practices for combination products, and review of promotional materials for products of all types. Additionally, she serves as an expert witness on FDA processes.

Saul B. Helman, M.D., is a partner and practice leader in Guidehouse’s Life Sciences practice. He provides support in investigations, litigation, and compliance integration matters involving healthcare and life sciences companies. Applying his knowledge, secured through working in international marketing and clinical development in industry, Helman has led projects involving expert witness testimony, litigation support, compliance implementation and assessment, and investigation support. He has led the support of clients and external counsel with investigations of fraud and abuse in industry.

Saul B. Helman, M.D., is a partner and practice leader in Guidehouse’s Life Sciences practice. He provides support in investigations, litigation, and compliance integration matters involving healthcare and life sciences companies. Applying his knowledge, secured through working in international marketing and clinical development in industry, Helman has led projects involving expert witness testimony, litigation support, compliance implementation and assessment, and investigation support. He has led the support of clients and external counsel with investigations of fraud and abuse in industry.

David Berger, JD, is a director in Guidehouse’s Life Sciences practice, where he leads the Regulatory Affairs, Quality and Patient Safety group. A lawyer by training, he has over 20 years of strategic leadership experience, including having served as general counsel for pharmaceutical and life sciences companies. Berger provides advisory support to life sciences companies related to FDA (and equivalent international agencies) regulations and requirements for bringing products (drugs, devices, and diagnostics) to market and keeping them on the market.

David Berger, JD, is a director in Guidehouse’s Life Sciences practice, where he leads the Regulatory Affairs, Quality and Patient Safety group. A lawyer by training, he has over 20 years of strategic leadership experience, including having served as general counsel for pharmaceutical and life sciences companies. Berger provides advisory support to life sciences companies related to FDA (and equivalent international agencies) regulations and requirements for bringing products (drugs, devices, and diagnostics) to market and keeping them on the market.

Jody Roth is an associate director in the Guidehouse Life Sciences team. She has over 26 years of experience in drug development as a regulatory and project management professional. Her expertise includes managing drug development from discovery to post-marketing phases across multiple therapeutic areas. She has spent the last 12 years in global development with an emphasis in the U.S. (FDA), EU (EMA),Canada (Health Canada), and Japan (PMDA), as well as exposure to emerging market regions including the Netherlands, Thailand, Korea, China, and Israel. Roth has obtained U.S. approvals for BLAs and supplemental NDAs and BLAs, as well as filed multiple INDs.

Jody Roth is an associate director in the Guidehouse Life Sciences team. She has over 26 years of experience in drug development as a regulatory and project management professional. Her expertise includes managing drug development from discovery to post-marketing phases across multiple therapeutic areas. She has spent the last 12 years in global development with an emphasis in the U.S. (FDA), EU (EMA),Canada (Health Canada), and Japan (PMDA), as well as exposure to emerging market regions including the Netherlands, Thailand, Korea, China, and Israel. Roth has obtained U.S. approvals for BLAs and supplemental NDAs and BLAs, as well as filed multiple INDs.