The Challenge of Influenza Drug Development: The First Step

Sam Venugopal, Frost & Sullivan

The influenza virus, which has caused hundreds of millions of deaths and illnesses through history, has puzzled scientists for hundreds of years. In 1500, Italians attributed the illness to the "influence" of the stars. Many historians believe that influenza was the main factor bringing about the end of World War I. During the 1918 epidemic, influenza killed between 20 and 40 million people worldwide.

Influenza virus: small, silent, sometimes deadly

While medical advances have helped reduce the severity of current influenza epidemics, the virus continues to cause large numbers of illnesses and deaths worldwide. In the United States alone the flu kills approximately 20,000 people and causes as many as 40 million illnesses each year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta), influenza and influenza-related complications are the 6th leading cause of death in this country, causing three times as many fatalities as AIDS. When factoring in the costs associated with outpatient care, hospitalizations, and the productivity lost through missed work and school days, the virus costs the United States $20 billion dollars per year. These numbers represent a lucrative opportunity for drug companies.

Developing an effective antiviral influenza drug, however, has turned out not to be trivial. Any new flu drug will be met with great debate and skepticism. Pharmaceutical companies hoping to introduce a drug into the marketplace will not only have to survive the inherent and obvious risks associated with drug development, but also must deal with the substantial economic, social, and political components of influenza management.

It has been 33 years since the first influenza antiviral drug—amantadine—was introduced in the United States. Despite its efficacy in preventing and reducing flu symptoms, central nervous system side effects have kept amantadine from general use. The lack of an effective influenza drug, coupled with the flu's often self-limiting nature, have engendered a feeling of indifference among doctors and patients regarding influenza management. Just 30–35% of those who contract influenza visit a doctor for treatment. Despite the introduction of rimantadine in 1993—a drug with a significantly better tolerability profile than amantadine—the influenza antiviral market has remained stagnant over the past few years.

Further complicating the issue and perhaps fueling the apathy associated with influenza treatment, about 60% of those who do go to the doctor for flu treatment are prescribed antibiotics, which are completely ineffective against viral infections.

The introduction of a new class of drugs called neuraminidase inhibitors represents the latest tool introduced to attack the influenza virus. Neuraminidase inhibitors work by attacking a viral site that is conserved through the influenza virus' evolutionary process. By blocking this site, the drug blocks an enzymatic function of the virus essential for the continual replication and subsequent spread through the influenza host's body. This mechanism of action provides an advantage over both amantadine and rimantadine, both of which are ineffective against influenza B. Because the neuraminidase enzyme is an essential function of both influenza A and influenza B, however, the neuraminidase inhibitors are show efficacy in treating both types of the virus.

Both Glaxo Wellcome Inc. and Hoffmann-La Roche Inc. introduced versions of neuraminidase inhibitors—amidst much media fanfare—in time for the 1999–2000 influenza season. While Glaxo's Relenza and Roche's Tamiflu do show potential, Frost & Sullivan believes that they do not offer the "complete" solution needed in order to change the way influenza is perceived and subsequently treated by medical practitioners. The drugs on average reduce the severity and duration of the flu by about 30%, about a 1 to 1.5 day reduction in the course of the flu's attack on the body. This minimal level of efficay has raised questions as to whether these drugs are worth the cost that they will impose on the health care system ($37–45/treatment). Furthermore, the requirement that both Relenza and Tamiflu be taken within 48 hours of the onset of symptoms presents another obstacle to their ability to transform the way influenza is managed within the United States.

Frost & Sullivan believes that current antiviral influenza drugs will fall well short of the hopes expressed by both drug companies and flu sufferers: These drugs will not become the blockbuster drugs within the realm of influenza management and treatment. Frost & Sullivan estimates that the neuraminidase inhibitor market will grow from approximately $25 million during the 1998–1999 flu season to $80 million for the 1999–2000 season. Although this represents a substantial gain, the growth exhibited will have more to do with a combination of marketing and promotional hype than to the actual efficacy of the drugs. Although these drugs will bring more awareness to the influenza treatment arena, the inherent restraints of the marketplace will prevent these drugs from achieving their potential growth rates.

Glaxo's Relenza (zanamivir) is delivered through an inhalation device known as the "Diskhaler."

The controversy surrounding Glaxo's Relenza is one such restraint. Stimulating the debate were negative comments made regarding Relenza during the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) regulatory review. The FDA advisory board recommended that the drug not be granted FDA clearance as it believed that the clinical trials did not show that the drug was significantly effective. In a rare move however, the FDA ignored the board's recommendation, approved Relenza for patients above 12 years of age, and consequently, sparked a heated debate over the drug. Great Britain's National Health Service and two of the United States largest health insurers—Humana Inc. and Wellpoint Health Networks Inc.—recently announced that their respective organizations would not cover the drug. All three organizations stated that they were not convinced of the overall efficacy and usefulness of the drug. Suddenly, fighting the flu ignited debates usually reserved for high-profile diseases such as AIDS and breast cancer.

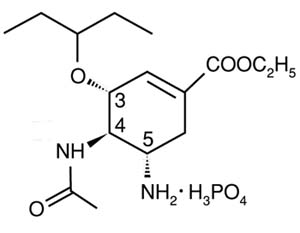

Molecular structure of Roche's Tamiflu (oseltamivir phosphate), available in 75 mg capsules

Clearly, getting these drugs accepted within the marketplace will require a mixture of more than just promotion and marketing. More importantly and key to the drug's success will be educating patients and clinicians about the drug's advantages and steps that must be taken in order to achieve those benefits. Before any of this can happen, Glaxo and Roche must realize that they have more than just a flu-fighting drug but instead, an unprecedented opportunity to change the way influenza is perceived and treated within the United States. These two companies have the chance to bring much-needed exposure to the area on influenza management and help build both Relenza and Tamiflu's market by changing the mentality of flu patients and doctors. It is very critical that Glaxo and Roche do not lose sight of this point if they hope to capture the lucrative rewards of the antiviral marketplace.

More details on the flu market is available in Frost & Sullivan report #5118, The United States Influenza Antiviral and Vaccine Market, 1996-2006.

For more information: Sam Venugopal, Biotech Analyst, Frost & Sullivan, 2525 Charleston Rd., Mountain View, CA 94043. Tel: 650-237-6588. Fax: 650-961-5042.