The First FDA-Approved Digital Pill — What It Means For Pharma

By H. Madannavar, J. Wang, and H. Chen, L.E.K. Consulting

Not a day goes by when we don’t learn of yet another application for mobile phones in healthcare. The list includes using mobile phones to diagnose and manage health-related conditions, to monitor subjects participating in clinical trials, and to conduct remote consultations with physicians and other caregivers.

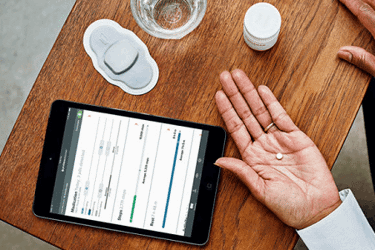

In mid-November 2017, the U.S. FDA approved what is perhaps the boldest use of digital technology in healthcare: a pill that is integrated with an ingestible sensor that captures information about whether the patient has complied with her medication regimen. A patient ingests the pill and it sends the data to a patch worn on her torso, which adds various physiologic measures. From there the information is wirelessly sent to a mobile phone app, allowing both the patient and her physician to track how the patient is using and responding to her medication.

We believe that the FDA’s approval of Japan-based Otsuka Pharmaceutical’s Abilify MyCite for certain psychiatric conditions — a first for digital medicine — will be seen as a landmark in patient-centered care. The problem that digital medicine addresses is profound. Approximately 50 percent of patients do not adhere to their medication as prescribed, taking it sporadically or with contraindicated foods or medicines, and 20 to 30 percent of prescribed medications are never even picked up at a pharmacy. This nonadherence problem varies in acuity depending on the disease and the population that is affected. The cost resulting from this waste runs into the billions of dollars in unused medication and, in addition, often more expensive medical care.

However, the benefits of digital medicine go beyond the saving of costs to the healthcare system. Over time, we believe that it can help solve three core problems — we call them gaps — bedeviling the development and the delivery of healthcare around the world.

For starters, it can bridge the outcomes gap. When physicians can track their patients’ compliance with a prescribed medication, and how patients are responding to it, they can manage their care better. The result is superior health outcomes. In fact, when precise information about an individual’s use of drugs is analyzed and then aggregated, healthcare professionals can gain much better insight about when to intervene with specific patients and how best to allocate nurses’ time with respect to prioritizing care based on need. Imagine Amazon.com algorithms applied to your health instead of your shopping.

Physicians benefit by being able to track their patients based on accurate, continuous data — their heartbeat and temperature, whether they’re sleeping or walking, and whether they’ve taken the right medication at the right time. And patients are empowered with that same data to become more engaged in their overall health. Health outcomes are most likely to be improved when health professionals and patients work in concert toward them.

Second, digital medicine holds the promise of bridging the access gap. In many parts of the world, in developed countries and particularly in developing countries, many patients live far from a modern physician practice or a large medical center. Digital medicine, by enabling the remote monitoring of a patient’s medical adherence coupled with physiological data, can alert a physician to events that may require intervention, such as a skipped dose or an alarming side effect. This dramatic improvement in a patient’s remote access to a healthcare professional holds the potential for upgrading the speed and accuracy of medical decision making.

Proteus Digital Health (which licensed the enabling digital pill technology to Otsuka) has been working to bring its platform to China. The following factors about China make the country ripe for digital medicine: A majority of the population uses the mobile messaging platform WeChat, and the capacity of healthcare services in both urban and rural areas is insufficient. The rollout of digital medicine in China will revolve around such mobile-powered applications, including telemedicine and remote consultations.

Third, digital medicine may also play a role in ensuring the sustainability of innovation. First, there is the sheer novelty of the technology: a pill joined with an FDA-approved ingestible sensor made of silicon, magnesium, and copper that captures critical data about whether we’re complying with our medications. Second, it securely and wirelessly sends this data to a wearable patch on the patient’s side that adds physiologic measures and transmits the combined information to a physician via the cloud. We expect it may take the healthcare world up to a decade to fully wrap its head around the extraordinary potential of digital medicine — how to value it, how to use it for optimal benefit, and how society should reimburse for it.

But getting back to the aggregated data it can yield — disease by disease, drug class by drug class, across different patient populations — digital medicine offers the potential to be used to select the right patients for a clinical trial or to better understand how patients respond to drug treatment. It can suggest new avenues of pharmacological research and support portfolio planners in their evaluation of assets and allocation of resources. It can significantly streamline and focus pharmaceutical R&D.

But the ability of digital medicine to bridge all the above gaps and become a global standard presupposes that it has achieved a critical mass: that doctors have adopted it, regulators are comfortable with it, patients are demanding it, and payers are covering it.

Here’s where two key challenges come in. Foremost, there is a degree of skepticism among pharmaceutical companies and some physicians. Pharmaceutical companies, like other large organizations, can be notoriously slow to integrate innovative technologies or platforms. Physicians, particularly those in large hospital systems, have barely enough face time with patients and even much less time to adapt to new care delivery models or new decision-making paradigms. Many of them will take a wait-and-see attitude toward digital medicine. A few early applications like Otsuka’s Abilify MyCite will raise awareness of the technology and speed its acceptance in the market. Other parts of the world — China, for instance — will likely be early adopters, leading the way in healthcare innovations, particularly ones that rely on mobile phones, apps, and social networks.

Another challenge is that privacy concerns may hinder adoption in some parts of the world. The concern may be greater in Western societies. Our experience in China suggests that volunteering of personal information, including health data, is prevalent, though the government has begun to explore privacy issues. Physicians’ attitudes will evolve over time, likely shaped by patients’ attitudes. U.S. and European patients quickly understand that they have control over who sees their data and that allowing a physician to see it reinforces the benefits that flow from digital medicine. We believe they may quickly start to demand access to digital medicine solutions.

One thing is for sure — we are entering a brave new world of patient-centered digital health. We believe that digital medicines will play an important role in the evolution of global pharma, from today’s industry that sells products and enables doctors to prescribe medications to tomorrow’s industry that offers servicing solutions and enables consumers to reach health outcomes in partnership with their care team.

About The Authors:

Harsha Madannavar and Justin Wang are managing directors and partners in L.E.K. Consulting’s Technology, Healthcare and Life Sciences practice. Helen Chen is a managing director and partner, and head of L.E.K.’s China Biopharmaceuticals & Life Sciences practice. Madannavar is based in San Francisco, and Wang and Chen are based in Shanghai.

Image credit: Proteus Digital Health