What Outcomes-Based Contracting Means For Drug Development & Drug Pricing

By Chris Lewis, Decision Resources Group

The mounting public outcry over drug prices — fueled by dramatic increases in cost for a few high-profile, older, life-saving drugs — has put intense pressure on the pharmaceutical industry to lower list prices and curtail price increases or face government controls.

One way the industry is responding is by diverting the national dialogue from price rollbacks to the notion of pay-for-value, which represents an area of common ground among healthcare policy stakeholders. The strategy aligns with healthcare payers’ focus on the total cost of care of their members and the pursuit of high-quality care — goals driven home by Medicare reforms that emphasize quality measurement and paying for value instead of volume.

The value discussion has intensified as drug development has shifted from primary care drugs to oncolytics and expensive specialty drugs, pressuring health plan pharmacy budgets. Health insurers and other healthcare purchasers are increasingly reluctant to pay for drugs that don’t work. That has led payers to experiment with outcomes-based contracts (OBCs) that hold pharmaceutical companies responsible for their products' real-world performance.

Some of the most high-profile drugs to hit the market the past couple of years — including the cholesterol-lowering PCSK9 inhibitor Repatha and the hepatitis C drug Viekira Pak — have become the subject of OBCs. In February, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, a Massachusetts-based health plan that had already inked a contract with Amgen on Repatha, announced another contract with Amgen for its rheumatoid arthritis drug Enbrel, which is facing impending competition from a biosimilar. The contract will tie the health plan’s payment for Enbrel to an effectiveness algorithm driven by six criteria, including patient compliance, switching or adding drugs, dose escalation, and steroid interventions.

The stars appear to be politically aligning to drive further growth of the pay-for-value trend. While the Trump administration has proclaimed a get-tough stance on drug pricing, it has also signaled its willingness to tackle the regulatory impediments that payers and drug companies say are holding back innovative contracting.

The commonly cited barriers — ranging from Medicaid best-price guarantees to anti-kickback rules to FDA regulations limiting the information manufacturers can share with payers — as well as the administrative difficulties of data sharing and collection, may be limiting the reach of risk-based contracting, but not stalling it.

More than one-third of the 40 managed care organizations (MCOs) surveyed by Decision Resources Group (DRG) indicated they were involved in OBCs, while another third said they expected to do such contracting in a year.

The increasing pressure for drug manufacturers to back up the value-proposition of their products by assuming financial risk underscores the importance of strategizing early in the drug life cycle about the potential of therapies to deliver positive, cost-effective outcomes outside of a randomized controlled trial setting.

As markets become saturated with efficacious drugs, MCOs are stepping up efforts to weed out “me-too” agents that are not differentiated in a crowded market. Developers whose therapies demonstrate positive outcomes among patients in the real-world setting will fare better in this market-access environment, particularly if the initial drug cost is offset by the downstream cost savings to the payer, such as reduced use of resources.

Payers Are Placing The Call

Our survey of MCO pharmacy and medical directors, conducted in September 2016, indicated that MCOs are taking the lead, more so than pharmaceutical companies, in pursuing OBCs, mostly to save costs, but also to improve outcomes. Such contracting works best for conditions for which drugs can concretely affect outcomes, and for which outcomes are objective and can be tracked and measured to the satisfaction of both parties. The strategy also tends to work best for drugs where high utilization intersects with high cost, as contractors typically need a large amount of data to work with and a drug or condition expensive enough to warrant the additional administrative costs.

One of the more common therapy areas for this type of contracting, as reported by our survey respondents, is cardiology. We chose to study cardiology after Novartis announced OBCs with Cigna and Aetna for its heart failure drug Entresto in early 2016. The drug company’s clinical trials showed that Entresto significantly reduced mortality and hospitalizations in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction compared to a standard-of-care ACE inhibitor. The contracts put the metrics to test in the insurers’ real-world populations. If the drug fails to live up to expectations, insurers get a discount on the drug.

Our study suggests other health plans besides Cigna and Aetna are participating in Novartis’ OBC for Entresto, indicating Novartis is confident payers will conclude that its branded drug, at a cost of $13.48 per day (based on wholesale acquisition cost), is worth paying for when other generic therapies are available for pennies per day. The quality of care improves for members, and insurers (and members) save money on expensive hospitalizations.

Show Me The Data

The specific features and results of outcomes-based contracts remain largely unreported publicly, but it’s no secret that such contracts are difficult to pull off technically and administratively.

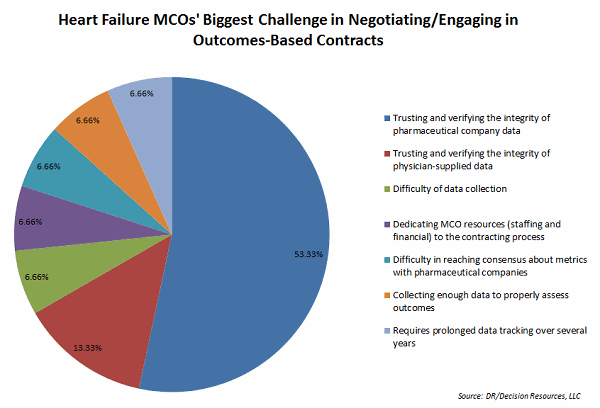

Many of our surveyed MCO directors say pharmaceutical companies can further the conversation on outcomes-based contracting by bringing adequate data to the table, suggesting that studies against comparators are useful. Yet these directors also say the biggest challenge is collecting necessary data and trusting and verifying the integrity of data supplied by the pharmaceutical industry. Another challenge is dedicating resources to the contracting process.

To track drug performance under the contract, MCO directors indicated they mostly rely on patient-level pharmacy claims data, but also medical claims data, which physicians may be asked to report.

While we found more payer participation than we expected in outcomes-based contracting, a high percentage of the cardiologists we surveyed either did not participate in an outcomes-based contract or did not know whether their practice did. But most of the specialists embraced the notion of value-based contracting and expressed a willingness to be a partner to such contracts. The cardiologists who reported participating in OBCs indicated they collect and report data, such as hospital use by their patients, patient compliance with medication regimens, and any drug safety issues that arise.

The Payoff Is Access

OBC contracts vary in their structure. Financial incentives, like rebate credits, are often promised to drug companies that meet contract requirements. Responses from payers indicate that the carrot most often dangled for meeting contracted outcomes is a favorable position on the formulary.

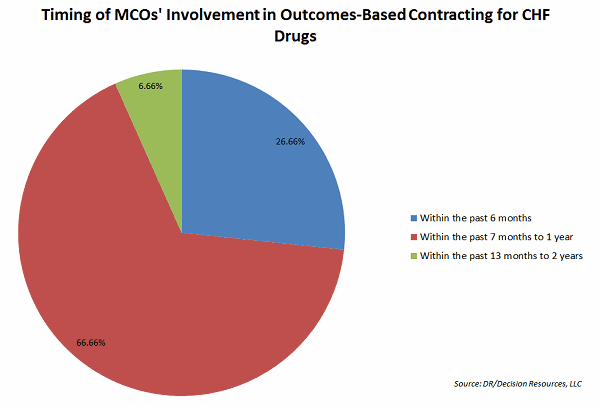

But even before results are determined, a drug is likely to sit in a good spot on the formulary throughout the contract, which typically lasts about two years, according to our respondents. Patients have access to the drug at a lower tier copay, with fewer prescribing restrictions, while the drug’s performance is being tested.

This easier access to the drug, likely the result of relaxed prior authorization rules, is cited by our surveyed cardiologists as one of the most important benefits to participating in an outcomes-based contract. Some contracts also encourage physicians to keep patients compliant with medication, which aids in the product’s longevity.

Cardiologists also told us they expect results of outcomes-based contracts to be shared with them, and most indicated they would be more willing to prescribe drugs that are demonstrated as clinically superior or cost-effective.

Plan Now For The Future

With the advances of Big Data and the integration of pharmacy and medical claims data, as well as attention on achieving regulatory safeguards, it’s safe to assume risk-based contracting will pick up. Companies can start by identifying the competitive landscape for the therapy early on, and by modeling the outcomes that can be tested in real-world patient scenarios to determine how the product will stand up to the rigors of a risk-based contract.

Looking down the road to potential contracts, the manufacturer should consider the key questions that will be part of the discussion:

- Does the therapy affect outcomes that are achievable and can be measured and demonstrated to the satisfaction of both parties? For instance, will the drug minimize the occurrence of hospital readmissions?

- Can the outcomes be achieved within a two-year period to address payers’ concerns that the plan benefits from the drug before their members might switch insurance plans?

- Does the manufacturer have the resources to help health plans monitor and report metrics?

- What is the acceptable potential upside and downside variance in performance?

- What is the potential for running into legal barriers from both the manufacturer’s and health plan’s legal staffs?

Pharmaceutical companies have been primed to make the economic argument for their products as healthcare decision makers increasingly look to health economics and outcomes research to augment clinical data in their formulary decision making. The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy strongly encourages manufacturers to include comparative effectiveness research studies — based on an active comparator — in their dossier submissions.

The news is good for manufacturers with defensible, differentiated products. They can circumvent the trend toward aggressive rebating the nation’s large pharmacy benefit managers has demanded to avoid being excluded from formularies.

As one expert on OBCs recently told me, manufacturers are already aggressively pursuing outcomes-based contracts, and companies that do not consider the potential for such contracting early in the life cycle of their product could get locked out of the market.

About The Author:

Chris Lewis is primary research manager, Global Market Access Insights, for Decision Resources Group. In her decade with the healthcare data and analytics firm, Lewis has authored numerous reports and given numerous presentations analyzing market-access issues affecting the pharmaceutical industry, including health insurance trends in large markets such as California, New York and Pennsylvania. She also authored the company’s series of profiles of U.S. pharmacy benefit management. A former journalist, Lewis holds a bachelor of arts in Communications from California State University, Sacramento.

Chris Lewis is primary research manager, Global Market Access Insights, for Decision Resources Group. In her decade with the healthcare data and analytics firm, Lewis has authored numerous reports and given numerous presentations analyzing market-access issues affecting the pharmaceutical industry, including health insurance trends in large markets such as California, New York and Pennsylvania. She also authored the company’s series of profiles of U.S. pharmacy benefit management. A former journalist, Lewis holds a bachelor of arts in Communications from California State University, Sacramento.