Thomas Jefferson Hasn't A Clue About Drug Development

By Louis Garguilo, Chief Editor, Outsourced Pharma

“I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.”

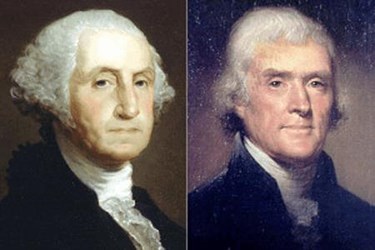

I’ve never much appreciated Thomas Jefferson. I’ve always been a fan of George Washington. Jefferson fled from battle; Washington fought for independence. Jefferson became a constant thorn in the first president’s side. Now, having found the quote above is attributed to Jefferson, I’m even less enamored.

Why? And what does this have to do with you, the women and men of the drug development and manufacturing outsourcing community?

Here’s one way to answer. Please take a brief moment to consider: What’s the outlook for success at your company? In your industry?

I’ll bet your mind quickly reached back as well as jumped forward. You began locating “historic markers” to help build your forward projections. Past and future are not in opposition. Jefferson was just blowing smoke.

Next consider the idea of fighting for a cause: Would you say that advancing potential drugs – and suffering the setbacks – through development, clinical trials, manufacturing, and eventually putting new medicines into the hands of patients, is a field for the less-than-committed?

Next consider the idea of fighting for a cause: Would you say that advancing potential drugs – and suffering the setbacks – through development, clinical trials, manufacturing, and eventually putting new medicines into the hands of patients, is a field for the less-than-committed?

Understanding what went before, and the steadfast resolve to get to the future, are invaluable for reaching success in our industry. An illustrative and teaching example of this – including the past and future of outsourcing – is embodied in a “thirty-year-old biotech,” as members of XOMA describe their company. We started tracing this journey with XOMA’s new director of development and manufacturing for outsourcing, Louis Demers, in the article titled, Are CMOs Sufficiently Serving Biotechs?. Our answer to that initial question: There are concerns they are not.

Here’s the rest of our chronicle.

Outsourcing’s Past And Present

XOMA was founded in the mid-1980s, making it one of the oldest “startups” in the biotech industry today. The company – currently with 80 employees, and located in Berkeley, California – is centered on “a diverse portfolio of innovative therapeutic antibodies.”

Its leading clinical candidate, XOMA 358, is a result of the company’s expertise in monoclonal antibody development, namely its XOMA Metabolic – or XMet – platform. XOMA 358, a “fully human negative allosteric antibody that reduces insulin receptor activity,” is in a phase two proof-of-concept (POC) study in patients with congenital hyperinsulinism (CHI), and a second phase two POC study in another rare indication, hypoglycemia post-bariatric surgery (PBS).

The company started out as a platform development group. “Obviously, we still have that technology, which is a proven discovery engine,” says Demers. “In the past, targets and molecules were either partnered out or developed internally.” He adds: “We weren’t focused necessarily on one area of a disease state. However, over the years – and particularly the last few – the company has made some significant shifts in focus.”

Many of those adjustments have to do with advancing opportunities for outsourcing.

Because XOMA started in a time predating our current era of outsourcing, it had to build the different capabilities necessary to do its own manufacturing of drug substance and product. “We’re talking about pilot plants, GMP manufacturing facilities, and even a 2700-liter fermentation suite, which at that time [mid-90s] was considered large scale,” explains Demers. “But building and maintaining these assets became less of an attractive proposition.”

Why? “The CMO world finally started to kick into full maturity,” he replies. And therein we have our first marker, helping paint a perspective on what biotechs faced then and now. Self-reliance equaled survival not so long ago. How quickly the times have changed.

“What XOMA also did in those years was build a bio-defense business with the DOD,” continues Demers. This, he explains, kept manufacturing up and running by feeding the in-house pilot plant and manufacturing capacity.”

Sounds like an excellent business plan, but here we meet our second marker: enter a new level and form of competition. Demers says the bio-defense business started to make less financial sense as time went on, particularly as more companies – including contract shops – started to proliferate and compete for the business.

Marker number three then enters via the unfortunate experience that may visit upon any drug developer. Last year, XOMA’s phase three program failed. “The company had to shift its operation fairly quickly,” explains Demers. “Management recommended and the Board decided it had to shed high fixed-cost operations. We started to focus on the strongest areas of the pipeline, in our endocrine business. And more aggressively bring in contract-service partners as a new business model.”

Faith In Future Service

Today XOMA is successfully activating that plan, and is back in phase two with two drug candidates. The company has continued to further its focus to treating orphan endocrine diseases. It’s been rapidly moving from internal operations to a broad-based outsourcer. What have been the challenges?

Demers says that from the technical-team perspective, there was already some experience and understanding of working with outside partners. “Where things needed to shift,” he says, “was at the actual selection of compounds, and not having the ability to rapidly go into a pilot plant to produce quantities of material. That lesser flexibility is part of the tradeoff with outsourcing for internal resources. We need a longer-term view of when we select compounds, and we plan a lot more in advance. We need to be more judicious.”

Of course virtual companies and biotech startups of the modern era won’t need to go through this adjustment. It is, though, interesting to note that when the startups of today bring in employees, they look for those who have had real-plant and manufacturing experience. Luckily, currently there are plenty of ex-pharma professionals to fit the bill. Should that change in the future, there will become an even greater reliance on outside partners. Or … dare I suggest … might we move back to companies with their own hard assets?

One more question, which will also bring us to our final marker, revolves around XOMA’s focus on orphan drugs, and the targeting of smaller patient markets in general. We visited this in our first article: Consolidation in the service sector – a “Big CMO” syndrome – may not be a fit for many of the innovator-drug developers today. These CMOs thrive on filling more capacity. The growing orphan-drug industry, as we all know, needs smaller volumes, less capacity, and greater flexibility.

“How does a future consolidated service-provider space fit with our orphan disease needs? We’re talking about one batch a year for a very rare compound, or one batch every couple of years even. For example, how does a CMO and sponsor keep staff trained on these compounds, and maintain a cadence that allows for the quality and assurance of the product supply, the same you might find for a product with multiple large-scale runs a year? I’m interested in understanding how the systems and CMOs are going to evolve to address that slice of the market.”

So are we. And the outcome looks to become a significant future marker.

-----

photo credit: http://porterbriggs.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Washington-and-Jefferson-300x200.jpg